The interview posted above is from SDPB's daily public affairs show, In the Moment with Lori Walsh.

Written by Joe Santos

that seventies show

Comparing the current U.S. economy, with its high and seemingly persistent inflation, with the U.S. economy of the 1970s, the decade of the so-called Great Inflation, is now common practice. Fixating on the comparison is understandable. For reasons I’ve discussed in earlier blog posts, high and variable inflation is pernicious in any case. Moreover, the Great Inflation ended in the early eighties with a costly double-dip recession during which, by my estimate, about 17 percentage-point quarters of real GDP were lost relative to where the economy stood before the contraction. The comparable figures for the Great Recession, which began in 2008, and the most-recent (COVID-instigated) recession are about 23 and 17 percentage-point quarters, respectively. Thus, the Great Inflation captivates us because of the high inflation rates the U.S. economy achieved; and because of the double-dip recession that effectively ended the Great Inflation. The latter was instigated by a Federal Reserve and its now-famous (or infamous) chair, Paul Volcker, who was determined to tighten monetary policy as necessary to return the U.S. economy to a steady state of low and stable inflation, something around 2 percent for example.

But is the comparison valid?

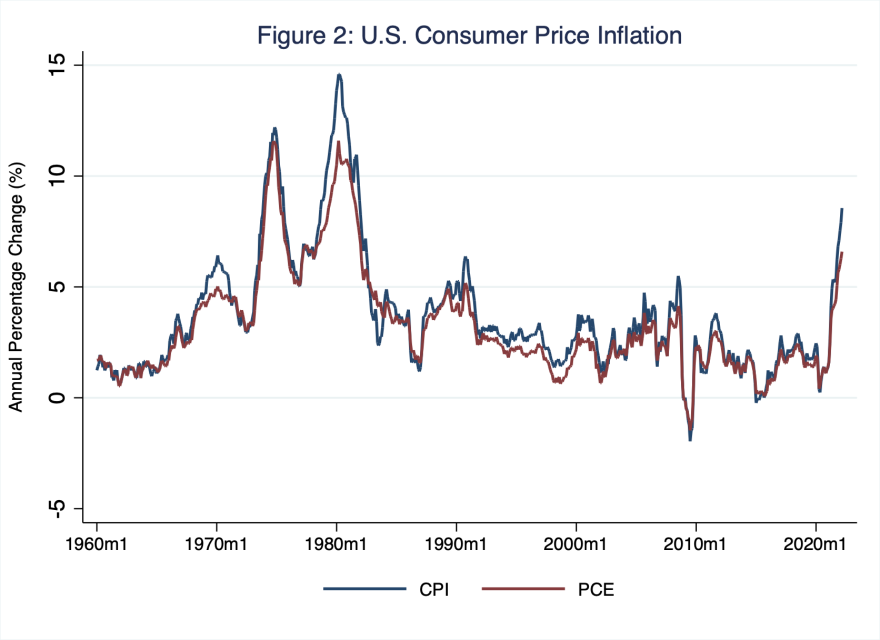

Empirically speaking, now may be too soon to know if the comparison is valid. Elevated rates of inflation in the U.S. since COVID have persisted for (only) about a year; whereas the Great Inflation persisted for the better part of a decade. Nevertheless, current rates of inflation are disturbingly high. As I illustrate in Figure 1, the year-over-year inflation rate based on either the consumer price index (CPI) or the personal consumption expenditures (PCE) index now registers above 6 percent: in March 2022, CPI inflation registered 8.6 percent, while PCE inflation, a measure the Federal Reserve prefers, registered 6.6 percent.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (FRED), series CPIAUCSL and PCEPI.

Thus, according to Figure 1, current rates of inflation in the U.S. are about three times higher than the rates we observed before COVID and during much of the decade that preceded it. In any case, while current rates of inflation are rising in ways reminiscent of the Great Inflation, we are not there yet. In Figure 2, I illustrate the same year-over-year inflation rates that I illustrate in Figure 1, but I begin Figure 2 in 1960 and, so, I include the period of the Great Inflation, which is starkly evident in the figure.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (FRED), series CPIAUCSL and PCEPI.

According to the measures of inflation I illustrate in Figure 2, during the Great Inflation, aggregate price pressures locally peaked twice: at about 12 percent (based on either measure) in the third quarter of 1974 and at about 15 (CPI) and 11 percent (PCE) in the first quarter of 1980.

Bad luck made worse by good intentions.

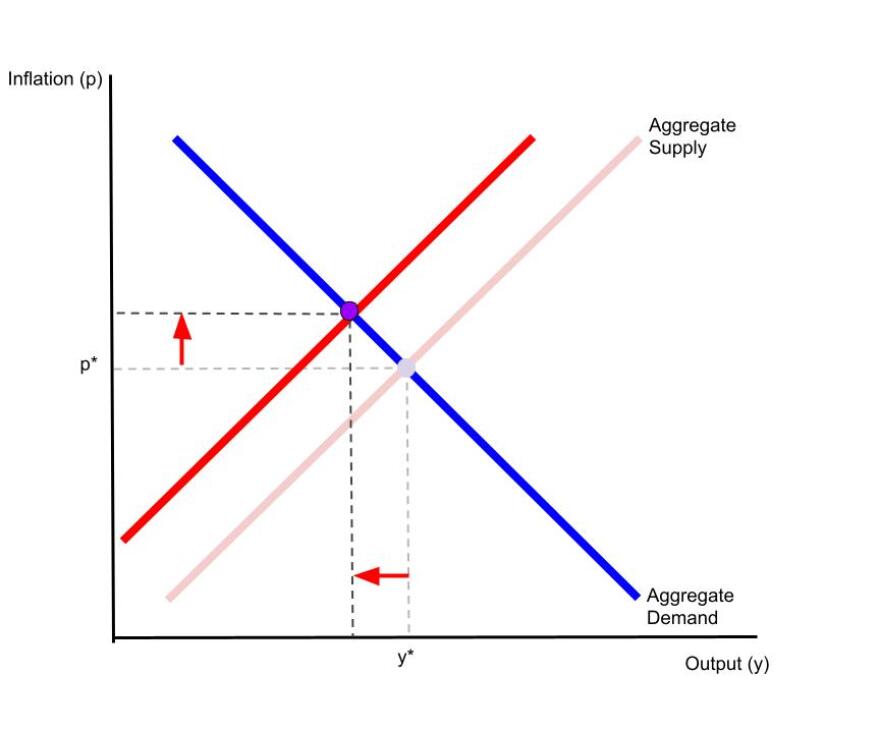

Theoretically speaking, the comparison of the current U.S. economy with that of the 1970s is valid because an aggregate-supply shock instigated each inflationary experience. In the early 1970s and to a lesser extent in the late 1970s, aggregate-supply shocks induced by geopolitical crises when the Organization of Petroleum Producing Countries and, later, the Iranian Revolution (1979) effectively reduced the supply of oil to a U.S. economy then-heavily dependent on foreign sources of petroleum. In the recent run up of inflation, an aggregate-supply shock induced by COVID buffeted the U.S. economy, of course. During both experiences, the outcome was a rise in inflation and a fall in output, followed thereafter by expansionary macroeconomic policies—CARES Act and near-zero interest rates during the recent experience, for example—that stimulated aggregate demand. Consider this theoretical comparison in the context of a simple macroeconomic general-equilibrium model, defined as the intersection of aggregate demand and aggregate supply, which I illustrate in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Macroeconomic Equilibrium and a Leftward Shift of the Aggregate Supply Curve

Briefly, and as readers of Schooled know well, in Figure 3, the horizontal axis measures output—think, real GDP—and the vertical axis measures the rate of inflation. The aggregate demand curve reflects the total amount of expenditures demanded by all sectors of the economy: namely, households, firms, governments, and foreign buyers of our goods and services. The aggregate demand curve is downward sloping in this space because, given some growth rate in the quantity of money circulating in the economy, the total amount of expenditures demanded falls [rises] as the inflation rate rises [falls]. The aggregate supply curve reflects the total productive capacity of the economy. The aggregate-supply curve is upward sloping in this space because, given the prices and quantities of the inputs to production, total output rises [falls] as the average price level of final goods and services rises [falls]. The intersection of the aggregate demand and aggregate supply curves simultaneously determines the equilibrium rate of inflation (p; vertical axis) and the equilibrium level of output (y; horizontal axis).

According to this model, inflation rises if either the aggregate-demand curve shifts to the right (because consumer confidence rises, for example) or the aggregate-supply curve shifts to the left (because of an geopolitical oil embargo [1973] or a pandemic [2020], for example). And, finally, monetary and fiscal policies shift the aggregate demand curve: for example, an expansionary monetary policy, which lowers the interest rate, shifts the aggregate-demand curve to the right, raising inflation and output.

During both the 1970s and COVID, aggregate-supply shocks instigated inflation by effectively reducing the economy’s ability to produce goods and services all else equal. This is to say, in the context of our model of a macroeconomic general equilibrium, the aggregate-supply curve shifted to the left in the way I illustrate in Figure 3, raising inflation and lowering output—the outcome is stagflation, in the parlance of the 1970s.

In principle, stagflation imposes on macroeconomic policymakers a very difficult choice: return inflation to its original level (p*)—this requires decreasing aggregate demand and further reducing output—or return output to its original level (y*)—this requires increasing aggregate demand and further increasing inflation. In practice, stagflation imposes on policymakers another problem: how to determine full employment, the maximum level of output the economy could produce without creating price pressures. During both the 1970s and COVID, policymakers responded to the “bad luck” of aggregate supply shocks with good intentions: expansionary macroeconomic policies and, specifically for the purposes of this blog post, expansionary monetary policies, without knowing precisely the level of full employment (Meltzer 2009, 844).

The U.S. experience post COVID remains (to this point anyway) different than the experience in the 1970s for at least three material reasons, one that bodes well for our current situation, and two that may not.

First, on August 15, 1971, at the end of a highly secretive three-day meeting at Camp David, President Richard Nixon effectively ended the U.S. dollar’s convertibility to gold; for an intriguing analysis of the three-day meeting and its aftermath, see Garten (2021). From 1944 until that day in August 1971, the Bretton Woods System prevailed: the system linked the U.S. dollar to gold at a fixed rate of $35 an ounce and the system linked other currencies, most notably those of the other G7 countries, to the U.S. dollar at fixed rates. Thus, by 1973—after failed attempts by the U.S. government and its international counterparts to restart a fixed-exchange rate system linked to gold—the end of the Bretton Woods System ushered in a modern flexible-exchange rate, fiat-money system. From that point forward, money effectively lost the intrinsic value it had when it was convertible into gold. (For more on exchange rates, see the Morning Macro segment, “A Tale of Two Currencies.”) In Figure 4, I illustrate the nominal exchange rates of the G7 countries with the U.S. dollar as the base currency (so the figure includes six as opposed to seven exchange rates, each relative to the dollar).

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (FRED), series CCUSMA02GBM618N, CCUSMA02DEM618N, CCUSMA02FRM618N, CCUSMA02JPM618N, CCUSMA02CAM618N, and CCUSMA02ITM618N.

On the far left side of Figure 4, the fixed-exchange rate system is clear from the relatively fixed nominal values—horizontal lines—of the currencies relative to the dollar and, reflexively, relative to gold. When the Bretton Woods System collapsed, these and other currencies floated freely (for the most part) and the link to gold was lost. Central banks, including the U.S. Federal Reserve System, were suddenly forced to operate monetary policy without the usual rules of the (fixed-exchange-rate) game, no matter that many central banks broke these rules from time to time. According to Meltzer (2009), “Learning to operate without a reserve currency tied to a commodity or with a fixed exchange rate proved difficult for central banks” (847). Put differently, absent gold convertibility or a nominal anchor such as a fixed nominal exchange rate, the credibility of the central bank’s strategic framework and the precision of its day-to-day policy tactics suffered, potentially contributing to high and variable inflation. For reasons that I will not address here, the current Federal Reserve System enjoys far more credibility as an inflation-fighting central bank than it did in the 1970s. Thus, this difference between then and now bodes well for our current situation.

Second, the Federal Reserve entered the 1970s in the final heydays of Keynesian macroeconomic stabilization policy based on the intellectual norm that a so-called Phillips curve—a trade-off between the unemployment rate and the inflation rate—existed and could be exploited by managing aggregate demand policy: ostensibly, policymakers thought they could essentially choose an unemployment rate and an inflation rate by simply managing aggregate demand accordingly. (For more on the Phillips Curve and its implications for macroeconomic policy, see the Morning Macro segment, “Revolutions.”) Of course, policymakers assumed they would stimulate the economy to full employment, but not beyond it—where, by definition, higher inflation lurks. The problem, then as now, is knowing where economic output is relative to full employment. Economic research on the Great Inflation suggests that monetary policymakers at the time systematically underestimated full employment; see, for example, Orphanides (2003). Thus, throughout the 1970s, the Federal Reserve maintained—unknowingly, to some extent—a policy that was too loose for too long. In Figure 5, I illustrate this difference between actual output and its full-employment level, or what economists call the output gap.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (FRED), series GDPC1 and GDPPOT.

According to Figure 5, for several quarters during the 1970s, the output gap was substantially positive, implying the U.S. economy was overheating, as it were, because macroeconomic policy in general—and monetary policy in particular—was inappropriately loose. By contrast, if the current output gap is to be believed (because these data are as yet unrevised), the current U.S. economy is not in the overheated state it was in during the 1970s. Indeed, trend price pressures, which I illustrate in Figure 6 (in red), remain lower today than in the 1970s, suggesting that inflationary pressures have not reached the level or breadth that such pressures reached in the 1970s; though, admittedly, given the recent rise in this trend, this pattern is hardly consoling.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (FRED), series CPIAUCSL and HP trend.

In any case, the U.S. experience in the 1970s instigated a (rational-expectations) revolution in macroeconomics that changed how we thought about macroeconomic policy and, specifically, the reliability of the Phillips Curve trade-off and output-gap data. Current monetary policymakers are less inclined than their predecessors to exploit the ostensible trade-off—a fool’s errand, based on the 1970s macroeconomic-policy experience. Thus, this difference between then and now may bode well for our current situation, though it is too soon to tell.

Third, the current 10-year inflation-adjusted (or real) Treasury yield to maturity is substantially negative, much as it was during the Great Inflation. However, the current real interest rate is larger (in absolute value) than it was at any time during the Great Inflation. In Figure 7, I illustrate this pattern.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (FRED), series GS10 and CPIAUCSL.

This difference between then and now does not bode well for the current U.S. economy, because a negative real interest rate of such magnitude indicates an excessively loose monetary policy, one that could push the U.S. economy past its full-employment level of output, driving the output gap positive and price pressures higher. Indeed, if there is any feature of the current U.S. economy that indicates we might repeat the errors of our Great Inflation ways, it is the feature illustrated in Figure 7.

For good reason, observers often compare the current U.S. economy with the U.S. economy of the 1970s. The two experiences are not identical, and how each experience differs from the other is instructive. During the Great Inflation, monetary policy was suddenly unmoored from a nominal anchor, causing central-bank credibility to weaken, the output gap was larger than the central bank estimated it to be, and real interest rates were, at times, negative so that monetary policy was very loose. Of these features of the U.S. economy during the Great Inflation, the third is most striking when we compare it to current circumstances: currently, the negative real interest rate is larger (in absolute value) than it was at any time during the Great Inflation. Meanwhile, although the current output gap is near zero, the gap is devilishly difficult to estimate in real time; thus, it may already be positive. Ultimately, current inflationary pressures are rising because monetary policy is too loose. Of course, the antidote to an excessively loose monetary policy is tight monetary policy, though hopefully not necessarily the sort that ended the Great Inflation by instigating a double-dip and costly recession.

References

Garten, Jeffrey E. 2021 Three Days at Camp David: How a Secret Meeting in 1971 Transformed the Global Economy (New York: Harper)

Meltzer, Allan H. 2009. A History of the Federal Reserve, Volume 2, Book 2: 1970 – 1986 (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press)

Orphanides, Athanasios. 2003. “The Quest for Prosperity without Inflation.” Journal of Monetary Economics, 50 (3): 633–663