This interview is from SDPB's daily public-affairs show, In the Moment, hosted by Lori Walsh.

Summit Carbon Solutions is planning a large-scale carbon capture and sequestration project in South Dakota, North Dakota, Iowa, Minnesota, and Nebraska. Chris Hill is director of environmental and permitting for Summit Carbon Solutions. SDPB's Lori Walsh talked with Hill about the science, business, and politics of the proposed Summit Carbon Solutions project.

The following transcript was auto-generated and edited for clarity.

Chris Hill:

The opportunity that we have in front of us is to capture a significant amount of carbon that is being emitted to the atmosphere currently from ethanol plants. We're targeting the CO2 that's coming from the ethanol fermentation process and is currently leaving the ethanol plant through a stack that the gas has gone through a scrubber first. And then it goes into the atmosphere through a stack. And so the opportunity is to be able to capture that CO2 and do a couple things — clearly realize the environmental benefit associated with CO2 not going to the atmosphere as a greenhouse gas, and then two — help with an additional revenue source or a margin uplift for the ethanol plants, which ultimately helps with crop values within the vicinity of those ethanol plants.

So ethanol currently procures, depending on where you're at, around 50% of the corn grown throughout the United States. This really provides some support for the crop value. And then also the land value that's also impacted by the increased crop value and the longevity of the ethanol plant operation.

Lori Walsh:

So carbon removal technology, not long ago, sounded like the stuff of science fiction. Can we put a fan and suck the carbon right out of the air, for example? But what you're talking about is carbon that is coming from the stack. Tell me how it works.

Chris Hill:

So the science behind it is relative straightforward. The fermentation process is used for a lot of different products, whether it's for ethanol, to create the ethanol itself for those alcohols that we can ultimately burn and combust in an internal combustion engine, or it's the same process used to make whiskey or other alcohols. So fermentation is not a new process. It's nothing new or all that complicated. The bugs eat the sugars or the starches that are from the corn. They ultimately produce alcohols. They release CO2 in that process. And that CO2 bubbles up through the fermentation tanks and ultimately leaves the tanks and it's currently being emitted to the atmosphere. So that's the science and where the CO2 is coming from.

Lori Walsh:

And how do you capture it before it comes out of the stack?

Chris Hill:

We'll be pulling the CO2 off its current emission point, which is the stack. And what we're doing with that is we're going to use multistage compression to pressurize the CO2 into a dense phase. And in the process, we're actually going to pull off moisture as well. So it's a very pure CO2 source, which makes it one of the most economic locations to capture CO2 because it's pure CO2, at ambient pressures, it's at ambient temperatures with little to no impurities.

Chris Hill:

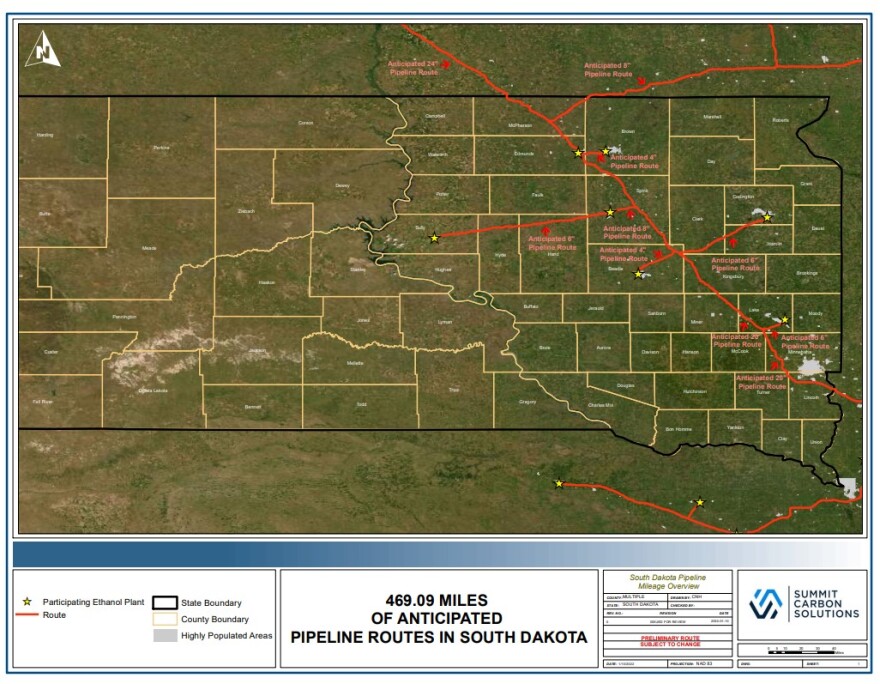

The impurities that we do see are water, oxygen, nitrogen. And so what we need to do is focus in on the water piece and pull that moisture out of the system so it doesn't cause issues in the pipe. And so we use multistage compression at the ethanol facility, or very nearby the ethanol facility. And after the CO2 is compressed into a dense phase or a super critical state where it behaves similar to a liquid, it's going to be injected into a pipeline that will range between four inches and 24 inches depending on where you're at in the system, ultimately to transport that CO2 up to North Dakota, just west of Bismark in the Oliver/Mercer county area, where it will be injected for safe and permanent sequestration.

Lori Walsh:

Why that location? What is it about the underground and the geologic formations that make that the place to capture this carbon?

Chris Hill:

The USGS has done a good reconnaissance study around ideal geologic conditions across the US. And North Dakota is blessed with some great sequestration rock. And what makes it great is its capacity to store that CO2 on a couple fronts. One, it means the right permeability. So when you inject that CO2 into the ground, it has a place to go. Two, is the porosity, which is just the pore space that allows the CO2 to accumulate in. And then three, is a cap rock. So a formation that has those, the permeability and porosity, and then also has a geologic formation above it to make sure that CO2 stays exactly where we're injecting it.

Lori Walsh:

How much for how long? How much can you store, and how long can you store it?

Chris Hill:

So the USGS's study estimates that the state of North Dakota has a capacity to store approximately 250 billion metric tons of CO2. So that's the USGS federal agency that has produced that study. So you take that 250 billion metric ton capacity in North Dakota. Our design capacity for our pipeline system is currently at 12 million metric tons per year. And so you can see by that number that the USGS calculated at 250 billion metric tons. And our annual capacity of 12 million metric tons you can easily calculate on the back of a napkin that there's, for at least our quantity of CO2 that we're going to be putting in place there, there's over 100 years of capacity in that area, or in the state of North Dakota.

Lori Walsh:

Is there a potential for that being reused with future technologies? What sorts of things are being developed to say there's a purpose for this and we can access it once again and use it? Anything on the frontier? We're back into science fiction, yeah.

Chris Hill:

So currently the plan is permanent sequestration. So everything we're doing is under the assumption that CO2 will never be removed from that geologic formation. So all our financial models, everything we're doing from a design perspective is for permanent sequestration of that CO2. Now, this is Chris Hill talking, but not necessarily a Summit Carbon position, but as a scientist, as an engineer, I get very excited about other opportunities for uses of CO2. Now, a lot of what would constrain the use of CO2 in our current business model is it has to be classified as permanent sequestration in order to get our revenue sources that we're counting on.

Chris Hill:

So the 45Q Tax Credit (Sequestration Tax Credit) is currently set up where you get $50 per metric ton of CO2 permanently sequestered. And then the low carbon fuel standards that we're, when we're able to reduce the carbon intensity associated with each gallon of ethanol that's produced, those ethanol plants can sell that ethanol into low carbon fuel markets like California, Oregon, and Washington, parts of Canada. And they can get a premium for it. But a requirement of that is to have verifiable proof that CO2 is being permanently sequestered and not released back to the atmosphere.

Chris Hill:

And so, for example, there are uses for CO2 right now that are being utilized. For instance, the production of dry ice, the use of that CO2 in the food industry like in soda pop. So those are some current uses. But if you think about those uses, those aren't classified as permanent sequestration. And they aren't counted towards the reduction of the carbon intensity score because ultimately, you're just delaying the release of that CO2 into the atmosphere from a dry ice, or a soda, or in another food or beverage. Whereas, when you inject it into a geologic formation for permanent sequestration, it's not going to get released back into the atmosphere.

Chris Hill:

If there were technologies out there that were economic and viable, where you could take the CO2 and you could turn it into a brick or a usable building material and it was classified as permanent sequestration, that opens up all sorts of possibilities. But without a project like the Summit Carbon pipeline and capture and all the infrastructure we're going to put in place, it's not as viable. But our hope is that through this project and other developments and science, that it opens up even more possibilities for potential beneficial reuse, like making bricks or what have you.

Lori Walsh:

So is the permanent sequestration environmentally benign?

Chris Hill:

So, yes. The permanent sequestration of the CO2 if you think about it, there's currently pockets of CO2 underground now. They were naturally generated. They're in geologic formations. Through the permitting processes, specifically the Class VI injection well permit process, where you have to go through a lot of science to verify that it's a safe area to inject CO2. You got to look for geological hazards, you got to take core samples, you got to do all your research, you got to have all your science. You're behind that permit. That's the assurance to the public that in fact, when you inject into these subsurface formations of it will be benign and safe.

Lori Walsh:

Is this a compliment to cutting emissions? Let's look at the big picture now and think about climate change and the impacts that it has. Is this one piece in a very large puzzle that partners with things like cutting emissions and reducing our dependence on fossil fuels? Is it a substitute for it? How do you see this from a big climate change picture?

Chris Hill:

For us, we're under no illusion that we're the panacea, or we're the end, or we're the only solution. This project is about doing our part and realizing that we are part of something larger and bigger from an environmental and economic benefits perspective. So, absolutely. There's a lot of other things that are going to continue to be done in this area. And we're putting a project together that will have a real and meaningful difference from an environmental standpoint, while simultaneously helping the ethanol industry, the agriculture industry, and these local communities that are so supported by them economically.

Lori Walsh:

I'm going to go back, Chris, to something you mentioned before about funding and the business model here. Is there a market for carbon capture? How is this being funded? Because that's always been one of the challenges that as technology exists, who pays for it?

Chris Hill:

Absolutely. So there is a huge market. From an investor perspective, there's so much interest in projects and investment opportunities that are aligned with the ESG (Environment, Social, and Governance) goals and metrics. So we hear companies like Microsoft, Google, Amazon, everybody wants to get to carbon neutral. Some folks can do that within in their operation. Some folks cannot do that within their operation, they need an opportunity to buy those offsets or those carbon credits to get to that neutrality. We're seeing a lot of momentum in that direction. So huge demand there. Now, let's not lose sight of the fact that there are some incentives that have been put in place by the federal government and state governments to get projects like ours off the ground. To get just enough inertia to where the full capital market can come in and really take hold of projects like this.

Chris Hill:

But so the funding, of course, all the dollars that we're using to construct, to design, construct and operate the infrastructure, that capital is private equity. So we have investors that are investing real dollars into the project. They've done their due diligence. They see the value here. They see the business opportunity. They see the environmental benefit. They want to be a part of it. So part of it is that those equity investors. The other part of it is debt financing. So just going to banks and supplementing the equity that we get from investors with loans from banks. And so that's where we're getting the capital.

Chris Hill:

So there are no federal dollars that are going into the capital side of it, but the revenue side with the 45Q Tax Credit. And then also the low carbon fuel standard markets that have been set up in California, Oregon, and Washington, they of course, are kind of that initial activation energy that the federal and state governments are trying to do their part to initiate projects and the whole carbon economy, which is foundational to make change and to see change. And we, and the ethanol producers, the agriculture community, the communities that we're going to be operating in will all benefit from that activation energy.

Lori Walsh:

We've talked about some big picture stuff. I feel like we need to go on the ground under the soil a little bit and ask some of those key questions that land owners want to know. First and foremost, what happens if the pipeline leaks?

Chris Hill:

There's so much that goes into making sure the pipeline doesn't leak. From a design, a construction and operational standpoint. And so I would be remiss if I didn't mention where the public and your listeners could go to find those requirements that are imposed on not just us from a carbon pipeline perspective, but all transmission pipelines across the US.

So I'd like to keep in mind that there's over two million miles of pipeline across the US that are regulated by the department of transportation. And specifically they're pipeline and hazardous material safety administration so PHMSA. And so when folks are looking for the regulations that apply to us and other pipelines across the US, they need to go to the DOT PHMSA regs. Specifically for us, it's 49 code of federal regulations part 195. And in that regulation, there are very strict requirements around what we need to do from a design, a siting, a construction, and an operation perspective.

Chris Hill:

So from a design perspective, we need to make sure we're following the appropriate factors of safety. We need to make sure that we're going through the right modeling, the right analysis. All of that is feeding into to the plan and in the project. On the construction side a few things that we have to do there is, every weld that we, as we're putting the pipeline together, PHMSA requires you to inspect 10% of those well. We're going to inspect 100% of them. So in some cases, we're going above and beyond. Also, on the design side, there's a requirement to go three feet from the top of soil to the top of our pipe. We're going to go a minimum of four feet. In a lot of cases, we're going to go deeper to minimize impact on current land uses, for example, the installation of tile or the future installation of tile. Or if we're crossing a river or a stream, things of that nature.

Chris Hill:

On the operation side, we have to do routine inspections. We have to have an integrity management program. We have to be monitoring the thickness of the pipe, making sure we have a leak detection system in place that can detect a leak. We have to walk the pipeline. We have to fly over the pipeline, take aerial imagery, thermal imagery to see if we can identify a leak. And then on a routine basis, we have to utilize tools that actually travel through the pipeline. One of them is called a smart PIG, which is just basically an instrument that is basically going through the pipeline, scanning the walls of the pipeline, seeing if there's any corrosion, any anomalies in the pipe, any erosion. And then we analyze that data. And if we see any leading indicators that there could potentially be a leak, we go and we remediate them before they become a leak.

Chris Hill:

And we have to have emergency response plans that are put in place prior to operations. So we develop those emergency response plans. We coordinate and develop them in collaboration with local responders and fast responders. So people know if there is an incident, how to manage that situation; how do we notify the public? How do we make sure the public is safe? How do we resolve that issue safely? So that's all done in advance. If you have a leak, there's a varying spectrums of leaks. So the most likely scenario would be no leak, but if there is a leak, it would be a small leak that could be detected either through just a noise that it would create, or a thermal footprint, because there would be, you would see a cooling effect on aerial imagery.

Chris Hill:

And then of course, through our regular inspection. And then the worst case scenario is a large leak. And a scenario that could play out there as if someone was working over our line with heavy equipment and they didn't go through and follow the regulations to call 811 to identify that there were pipelines, ours or other pipelines in place, and somebody struck the pipeline, there would be a release of CO2 of greater magnitude in that scenario.

Lori Walsh:

Worst case scenario, is it gas, fire, liquid, what? What happens in the worst case scenario?

Chris Hill:

So the characteristics of CO2 is it's interesting from a relative standpoint, it has a lower risk profile than a lot of other products folks are used to in a pipeline.

Chris Hill:

Because it's not flammable. It's not explosive. In fact, CO2 is used in fire extinguishers to put out fires. And so from that standpoint, it has a lower risk profile. But it's in dense phase in the pipe, but the moment that CO2 is released into the atmosphere and it is within atmosphere pressures, it immediately turns into a gas. And so it won't seep into aquifers. And it naturally wants to disperse within the air and equalize with the concentration of CO2 in the air itself.

What I don't want to do is be dismissive of the risk. There are risks with this pipeline, just like there's risks with any pipeline. CO2, although it's not combustible or flammable, it can displace oxygen. And in that case, it would be an asphyxia and someone could get really harmed and there could be a fatality. And so we have to respect that. We have to understand that. And we have to acknowledge that. And so I want to make sure I'm very clear.

Lori Walsh:

When you build the pipeline, what sorts of things do you do as you move through land-owner space that you've agreed to move through as you make those deals with land owners? You're going through a lot of Agland. You're going through a lot of environmentally sensitive places. How do you do that well?

Chris Hill:

It starts off way before you get out there and you do the construction. It starts off when you start planning your route. And so the whole routing process is designed to minimize environmental, cultural, and of course, land-owner impacts. And make sure you take into consideration future land uses, et cetera. And so the first thing we do as a company, Summit Carbon does, is we know we need to get from point A to point B. We have our ethanol plants. Those are point A, and we have an idea of where we want to get to from a sequestration standpoint based on geology.

So the next question is how do you do that and meet those objectives of minimizing impact to those people, or features; environmental or cultural features? But you go out and you round up as much publicly available information as you can.

Chris Hill:

So there's a lot of data out there. And you develop an optimum route based on publicly available information. And that's your first step. And then your next step is you start reaching out and you start finding proprietary information, confidential information. One example of confidential information that not everybody has access to is cultural features that have been identified and disclosed to the state historic preservation offices. So you have to have very specific licenses and you have to have qualifications to get that information. And so we gather that proprietary and confidential information.

Chris Hill:

And then the next step is to release your route out to the public, to communities, to land-owners. Letting them know what you're trying to do and why you're trying to do it. And then you get even more information from those communities, from those land-owners. And it's an iterative process where you're ultimately trying to come up with this optimized route, trying to balance multiple criteria, and factors, and just navigate around different objectives and trying to find that best solution. And it's not always the cleanest process. And everybody sees the world from their individual perspective. And what we're trying to do is mediate that process and get to that best, most optimized solution in the least disruptive way.

Lori Walsh:

All right. Go ahead.

Chris Hill:

And in that process, we also have field verification steps. So for instance, I'm in charge of managing an environmental survey crew and a cultural survey crew. So in addition to collecting information that is accessible online, or through government agencies, or through confidentially, through agencies, and from land-owners, we have to send out qualified biologists to get out in the field and they need to look and delineate wetlands, they need to look for habitat for threatened and endangered species.

And as they're doing that, we're constantly bringing that information in, and we're making decisions and changes based on that. Same on the cultural survey standpoint. So we have teams of archeologists that are walking our right of way and surveying parcels where we have land-owner permission to survey those lands. And they're looking for artifacts, for cultural features, areas of cultural significance.

Chris Hill:

And as they give us that information, we're making decisions to avoid those features, minimize impact either through changing where we're putting the line, or even considering different construction methodologies like horizontal directional drilling. And so there's just a lot of field verification that's going along with that as well. Something that I'm very proud of as part of the project and related to cultural survey is from the get go, we sent invitations to 62 tribes across the country that have the potential to have ancestral rights or history to where our project footprint is.

Chris Hill:

And we invited them to participate and provide tribal monitors with our cultural survey crew. So in addition to what we are identifying using Western techniques, we're also providing the opportunity for the tribes to help us identify things that wouldn't necessarily be on our radar and participate in the routing process from the get go. And that's been very effective and we've really appreciated that participation. But a lot is going into the routing a lot of different perspectives. And we're here to just collect that information and come up with this optimized solution and route.

Lori Walsh:

And tribes have responded to that?

Chris Hill:

Yes.

Lori Walsh:

To those invitations in the affirmative?

Chris Hill:

Yeah. We had 21 tribal monitors that were out on, that participated in our 2021 survey. And that was 21 tribal monitors from seven tribes across the five state footprint. And we've had a couple conversations since then that we expect even more participation in 2022, which we're very excited about.

Lori Walsh:

You've been really generous with your time and this is of course a big story. So I want to wrap up and let you go on. But I am curious to ask you as an engineer, working in this field in a time when science can be very difficult for people to understand and there are a lot of science skeptics. It's not quite as clean cut as it was before. People have a mistrust of data and of scientists like yourself. And of course, it's a politically really divisive time in our nation. Are you finding that as you try to do your work? That there are obstacles that maybe you wouldn't have had a few years ago as you try to explain to people how this works?

Chris Hill:

There are obstacles and there's varying education levels. And it's upon us, Summit Carbon, or any project trying to do ... I don't care if it's a carbon CO2 pipeline, or capture pipeline, or an oil pipeline, or natural gas pipeline. We have an obligation to meet people where they are. And to do the best we can to educate them. I personally find it challenging when I'm trying to provide objective factual information and there is so much skepticism based on past experiences. It's hard to have a healthy conversation around this topic. But at the same time, I'm empathetic to folks that have concerns because they are founded in past experiences and science is all about healthy skepticism. The whole scientific method, everything we do is about critical thinking.

Chris Hill:

And so I love that. And I love a healthy dialogue, healthy conflict, a good debate. But when it gets political and folks are, they're passing along misinformation just to create fear and confuse the public for their own agenda, their own purpose, that's just something I really struggle with. And we are seeing that across the project. And all we can really do is try to reach out to as many people as we can, develop trust, a good relationship, and treat them fairly and be honest and transparent. And that's what we're trying to do. We, I think, didn't realize how hard that challenge was from a technical, from a scientific standpoint.

Chris Hill:

We thought it was pretty clear and folks were going to be excited about this magnitude of project and the benefit to the environment, the clear benefit to the agriculture industry, the clear benefit to the ethanol industry. And then, of course, to the communities that we're impacting. It hasn't been as clear cut as that. And so we're having to ratchet up a little bit our outreach, our PR, our media relations, and our land-owner relations and do better. But we're up for the challenge, and we believe in what we're doing. And we believe in the benefits that I just mentioned. And so it's not easy, but it's worth it. It's worth it to us and we're happy to do it.

Lori Walsh:

Chris Hill, thank you so much for spending so much time talking about all of this. It's been fascinating.

Chris Hill:

Anytime. I appreciate your opportunity and I can't thank you enough. You have a very important role in this project. Getting good, scientific, objective information out to the public, and good reporting, it's just incredibly valuable. So thank you for what you're doing. And anytime you need my time or you need anything from me, I'm happy to give it.