The South Dakota Historical Society chronicles the history of Presho in the early 1900s.

Dorthy Schwieder

South Dakota History, volume 30 number 2 (2000)

South Dakota History is the quarterly journal published by the South Dakota State Historical Society. Membership in the South Dakota State Historical Society includes a subscription to the journal. Members support the Society's important mission of interpreting, preserving and transmitting the unique heritage of South Dakota. Learn more here: https://history.sd.gov/Membership.aspx. Download PDFs of articles from the first 43 years and obtain recent issues of South Dakota History at sdhspress.com/journal.

On an early spring day in 1909, as the train on the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul & Pacific line screeched to a stop at the Presho station in central South Dakota, two young men alighted, eager to look over the local business activity. Brothers Walter Hubbard and Jack Hubbard, ages twenty-seven and twenty-five respectively, surveyed a promising scene. The railroad had reached the small village in 1905, creating a business boom, and by 1909 Presho claimed more than six hundred residents. The town bustled with activity as new families arrived daily, some to reside there and others to buy supplies before heading out into the countryside to homestead. The Hubbard brothers soon decided that Presho's future prospects looked good. Within three years. Jack would return to eastern South Dakota, but my father, Walter George Hubbard, would remain. Over the next four and one-half decades, he would operate several businesses, marry twice, and raise a family of ten children. Jack's short stay was typical of other early Presho residents; Walter's lengthy tenure was not. Dozens of entrepreneurs and businesses would come and go during the first decades of Presho's existence, but only a limited number would survive and persist.

Walter Hubbard, according to western historians, would be a Great Plains town-builder. Although I am confident my father never heard the term, he nonetheless fit the description. He and countless other businessmen and women, professionals, craftsmen, and general laborers, some single and some with families, developed hundreds of communities on the plains. Townbuilders played a vital role in building up the retail trade centers that served the homesteaders coming to take up land. Moreover, they provided a collection point for the goods being shipped in and agricultural produce being shipped out of the community. Over time, these same individuals and their families helped to establish churches, schools, and other facilities. While farm families were equal partners in the economic development of an area, it took the creation of towns, ct>mplete with social, religious, and educational institutions, to signify progress.

The town-builders who settled the Great Plains faced a multitude of hardships from an environment that could be less than hospitable. As many scholars have observed, plains towns suffered economic instability because the region was only marginally suited to its main industry—agriculture. Average precipitation on the Great Plains varied from state to state, but overall the region received less precipitation than farther east. In fact, the area west of the Missouri River in South Dakota, with an average yearly rainfall of only fourteen to sixteen inches, was classified as semiarid. In the fifteen years from 1903 to 1920, west-river residents experienced both wet and dry periods; specifically, heavier than average rainfall Lintil 1909. but then extreme drought for the next two years. For the rest of the decade, until 1920, residents experienced a mixture of good years and bad. Given the fickle environment, plains communities experienced constant population turnover and business instability.

While many historians have focused on the Great Plains environment and its impact on development, particularly agriculture, a far smaller number have examined the economic and social development of the region's small towns. John C. Hudson and Paula M, Nelson, in particular, have studied plains towns and made a number of observations about the persistence, fluidity, and occupational changes of the business classes. Nelson, in her recent book, The Prairie Winnoivs Out Its Own: The West River Country of South Dakota in the Years of Depression and Dust, referred to the west-river town of Kadoka as having "a Main Street in constant flux" because residents frequently changed occupations or merged businesses. Hudson, in his study of North Dakota communities titled Plains Country Towns, writes, "fluidity was the norm and persistence the exception.

Given the region's inherent geographical and climatic difficulties, periodic out-migration from small plains communities was a fact of life. Only those towns that kept a core of businesses sufficient to maintain a vital main street during times of exodus would be able to attract new settlers later and sustain their total populations over time. In this sense, the business people who persisted played an indispensable role. Using the federal censuses of 1910 and 1920, along with accounts from three Lyman County histories, it is possible to examine the backgrounds and experiences of the men and women involved in Presho's businesses, professions, and trades, and to analyze the changes in occupational groups and persistence rates that occurred between those years.- In this way, we can discover who these men and women were. What were their ages and marital status? What gender distinctions existed in the business community-? Which business owners exhibited the greatest persistence and for how long?

The towns that grew up on the plains often came about because of railroad expansion. Presho was one of fifteen communities linked together by the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul & Pacific Railroad between Mitchell and Rapid City. The town grew quickly with the arrival of the railroad and its subsidiary, the Milwaukee Land Company, which platted twelve blocks and auctioned off the lots on 9 November 1905. That same day, a bank opened for business, and merchants began displaying goods. Within six months, according to local history, "a very creditable looking town was erected, with both sides of Main Street built solid for about two and a half blocks, with some places of business on side streets." About the same time, a small residential area began to take shape along both sides of Main Street, extending south

Walter and Jack Hubbard appear fairly typical of the town's early arrivals. Their parents, Maggie and Augustus Hubbard, had immigrated to South Dakota from County Armagh, Ireland (now a part of Northern Ireland), in 1879. The couple had one daughter born in Ireland and eight more children after arriving in Davison County, where they homesteaded 160 acres and purchased an additional 200 acres six miles north of Mitchell. Augustus Hubbard also sold real estate in the area. From all accounts, the elder Hubbards were successful. Walter, Jack, and three other siblings all finished common school and attended Dakota Wesleyan University for several .sessions. Afterwards, three sons, Walter, Jack, and George, returned to the farm, taking over its operation when their parents retired to Mitchell in 1905.

By 1909, Walter and Jack had decided that the business world offered greater opportunities than farming. Of the new communities developing west of the Missouri River, Presho had much to recommend itself to aspiring entrepreneurs. With over six hundred residents, it was the largest town in Lyman County. Kennebec, nine miles to the east, and Vivian, twelve miles to the west, imposed some limits on the Presho trade area, but with small communities extending a number of miles to both the north and south, the potential trading area seemed extensive. Equally important, the town contained a wide variety of businesses and professional persons, including physicians, lawyers, a dentist, newspaper editors, general merchants, bankers, real estate agents, an undertaker and furniture store operator, a building contractor, a baker, and jewelers. In typical railroad-town fashion, two hotels, two lumberyards, and a grain elevator clustered near the train tracks. In short, Presho appeared to have sufficient business people, tradesmen, and general workmen to provide almost any service needed.

One year after the Hubbard brothers arrived, the federal government conducted the census of 1910, Presho had 635 residents. Typical of frontier communities, males outnumbered females, 346 to 289, and the population was relatively young. The average age among the town's professionals (three lawyers, two physicians, two pharmacists, one dentist, two newspaper editors, twelve teachers, two nurses, and two clergymen) was below thirty. Presho's merchant, proprietary, and managerial class, totaling forty persons, was somewhat older, with an average age of forty. The town included 164 households, and 6 households were headed by females." At first glance, the 1910 census data seems to indicate that persons locating in Presho decided wisely. After all, the town had maintained both a stable population and a diverse business community for almost five years. A closer look at the figures, however, reveals great fluidity within the town itself As Nelson and Hudson discovered in other plains communities, Presho merchants, tradesmen, and service people were constantly changing occupations, organizing new partnerships, or merging business interests.'

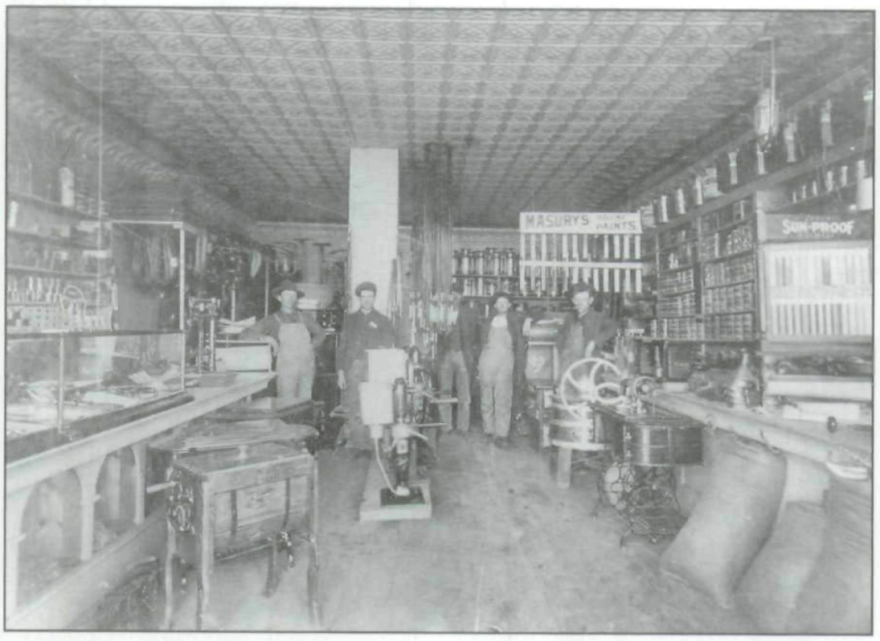

My father's business interests reflected that fluidity. Immediately after arriving in Presho, Walter and Jack formed the Hubbard Brothers and Morris Implement Company in partnership with George R. Morris. The three men sold John Deere farm implements, traction motors, farm wagons, cream separators, and buggies. Morris had arrived in Presho at the time of the towns founding and quickly filled a niche by constructing the Arcade Hotel. As a result, he was probably able to bring more capital to the partnership than were either of the Hubbards, although the details are not known.'' According to Hudson, most people starting businesses in Great Plains towns were "deeply in debt, short of working capital and unable to do much about their plight until local farmers had been paid for the next harvest. One means of increasing capital was to acquire a new business partner. This practice appears to have been so common and informal that it is difficult to trace through business records. The Hubbard-Morris arrangement may have called for the brothers to run the business while Morris worked elsewhere, for he is not listed in the 1910 census even though the partnership was still in effect.

The Hubbards and Morris remained in business for about three years, during which time they dropped the John Deere line and acquired an International Harvester dealership. In 1912, Jack Hubbard married another Presho resident, Rosa Hagler, and returned to the Mitchell area to farm. Morris relocated to Lincoln, Nebraska. Walter, apparently, had saved enough money to buy out both partners. To supplement his income, he maintained a cream station, where he collected and tested cream before shipping it to Mitchell by train. He also carried mail on the star route northeast of Presho, making deliveries by either horseback or motorcycle depending on the weather.' In 1913, he formed a new partnership with Glen Andis, who had arrived in Presho six years earlier. Under the Hubbard-Andis Implement Company name, the two men carried on a number of enterprises until 1920, including selling International Harvester equipment and Chevrolet cars and maintaining a livery stable. They also rented automobiles to prospective land buyers who wished to tour the area. The Hubbard-Andis partnership was typical of other early railroad-town businesses in that nonspecialization was the norm.

For Glen Andis, the partnership was only one of many business interests. Born in Tarkio, Missouri, Andis first came to Presho in 1906 to homestead. His father accompanied him on his initial trip west, and the men arrived by rail when Presho was still the end of the line. While the train took on coal and water and turned around to head back east, the younger Andis suggested they go to a nearby hotel for pie and coffee. His father, however, would have none of it, stubbornly remaining on the depot platform for fear of being left behind. He was not going to "spend any more time than he had to in what he thought was the most desolate. God-forsaken place in the world," a granddaughter later wrote. Glen Andis stayed, however, and after proving up his claim, he sold real estate, served as street commissioner, worked as postmaster for eleven years, and operated a Gamble's store for over twenty years, all in addition to his partnership with Walter Hubbard.

Andis's experience well illustrates town residents' penchant for change in occupations and underscores another characteristic of Presho's town-building class. Many studies of frontier communities present town-builders and homesteaders as two distinct groups, but a sizeable number of Presho's business class were homesteaders, as well. Some, like Andis, proved up before moving to town and entering business, while others reversed the process. Some people wore two hats, homesteading and operating a business in town at the same time. B. R. Stevens, like Andis, typified the first type of town-builder, homesteading in the area even before Presho was platted. He later moved his family to town, but they remained there only a short time. After a four-year sojourn in Nebraska, Stevens returned to Presho to take over a furniture and undertaking establishment. In 1927, he took a trip to California, and sensing there was money to be made in providing lodging for travelers, he then opened a cabin court and filling station in Presho along United States Highway 16.

Herman and Anna Jost, who opened a jewelry and china store in Presho, followed the same pattern. Like many early Presho residents, they had been born in Iowa. The couple had started out farming near Marcus, but by 1888, Herman Jost had purchased his first jewelry store in Remsen, where he learned the watchmaking, gold soldering, and optical business. In 1903, the family moved to Lyman County and homesteaded three miles north of Vivian. Two years later, they moved to Presho, where they operated their jewelry and china business for the next forty years. Other businessmen who arrived in Presho along the same route included John B. Jones, a former homesteader who operated a real estate and insurance business and had an interest in neighboring towns, as well. C, K. Knutson obtained land through a lottery in October 1907 and a short time later moved his family to town, where he began working in a meat market; he I'Knight the business six months later but also kept his farmland About the same time, Joseph E. Stanley of Bridgewater filed a claim southwest of Presho. While attending Dakota Wesleyan University, he became acquainted with Mae Alfson, who arrived in Lyman County in 1905 with her older sister, Freda, to file on homesteads near Stanley's. Like many other single, female homesteaders, both women taught county school. Mae Alfson and Stanley married in 1908 and combined their homesteads. After a short stay in Oacoma, they made their permanent home in Presho, where Joseph Stanley opened a real estate office and continued farming.

Richard Sehnert, another homesteader-turned-town-builder, immigrated to the United States from Germany and settled in Lyman County with his wife, Anna, and their first three children in the early 1890s. The Sehnerts homesteaded for a time near

Dirkstown and later moved to a farm south of Oacoma, near the mouth of the White River. Unhappy with farming and being a baker by trade, Sehnert decided in 1906 to pursue that occupation in Presho, Along with his wife and eight children, he set up a bakery, restaurant, and lodging facility. The business was a family affair, with one daughter working as a clerk and another daughter as a waitress. Sehnert continued the business until his death in 1924.

The homesteader/town-builder who perhaps demonstrated the greatest diversity in his business career was Charles S. Hubbard (no relation to the Waiter Hubbard family). Charlie Hubbard arrived in Lyman County to homestead sometime before 1905; his future wife, Mildred Thompson, arrived about the same time to stake a claim and teach rural school. With Presho's founding, the Hubbards, now married, moved to town, where Charlie opened the Blue Front Liveiy Stable, A year or so later, the railroad dug a well on Presho's east side, creating a small lake. Sensing the commercial possibilities, Hubbard opened a bathhouse and provided boats for rent. He next went into the hay business, hiring men to cut and bale the area's high-quality grass, which brought substantial prices back east. In fact, in 1915, a record twenty trainloads of hay were shipped out of Presho. Charlie and Mildred Hubbard would take on yet another business venture in the 1920s, when they constructed a cabin camp and roominghouse along United States Highway 16, operating it into the late 1940s.

Philo S. Chapman took a somewhat different approach to combining his town-building and homesteading careers. In 1906, Chapman, his wife Jesse, and their two children arrived in Presho, where he managed a local lumberyard. His daughter later recalled that when he learned the following year that the federal government was opening the Lower Brule Indian Reservation north of Presho for settlement, he "had his mind on a homestead.'' Chapman took a claim, built a home with "two rooms upstairs and two down with a trap door in the kitchen to go down to the cellar," and moved his family in November 1907. He continued managing the lumberyard, at first trying to drive back and forth to town each day. The arrangement proved too difficult. However, he soon fixed up a room for himself behind the lumberyard where he slept during the week. Because Jesse Chapman was uncomfortable staying on the claim alone with their three young children, the lumberyard manager hired a woman to live with them during the week. In the fall of 1908, the Chapmans proved up and moved back into Presho.

Skilled workmen sometimes wore two hats, as well. James Terca arrived in Lyman County in the spring of 1905 to homestead south of Presho, near the White River. Terca also worked at M. E. Griffiths's blacksmith shop, staying in Presho during the week and walking the seventeen miles to his claim on weekends. After the first month, he was able to buy a horse and toward the end of the summer had sufficient money to purchase another horse and a buggy, which made traveling to and from town much easier. Another tradesman, Frank L. Brooks, homesteaded near Presho and worked in town as a carpenter. He helped construct the town's first schoolhouse and later purchased the harness shop.

Social class appeared to be no barrier to the practice of combining town activities with homesteading as all types of people took up claims in addition to their other callings. Dr. L. Benjamin Seagley, age forty-seven at the time of the 1910 census, arrived in Presho sometime before 1909 to open a medical practice. In 1909, the Presho mayor appointed him as the town's health officer. At the same time, Seagley also filed on a claim south of town where his wife and two daughters resided and his wife conducted school for a period. In the experience of the Seagley family, as with many other plains residents, geographical mobility was constant. Seagley and his wife had both been born in Indiana; their oldest child was born in Illinois; and the second child was born in South Dakota in 1901, an indication that the doctor had practiced elsewhere in the state before coming to Presho. Shortly after proving up on their claim, the family left Lyman County. Another professional who combined activities but stayed longer was Frank E. Mullen, a former high-school principal from Randolph, Nebraska, He came to Lyman County with his wife, Anna, in 1906. In addition to opening a real estate business, the Mullens homesteaded eighty acres southwest of Presho and another eighty acres in Lund Township. Four years later, they moved to Presho, where Frank Mullen hung out his law shingle and practiced until his death in 1923.

It is difficult to determine precisely why some persons chose to both homestead and operate businesses or to discern which activity first attracted them to the Presho area. "The land had a powerful appeal," according to historian Paula Nelson, "and the terms on which it might be had appeared easy. Residency rules were lenient, so homesteaders could leave the claim for extended periods to work or visit elsewhere." As long as homesteaders spent "occasional nights" in their dwellings. Nelson notes they could claim legal residency. During winter, settlers could visit their claims for only a few days and still comply with the residency rule. Because homesteading requirements enabled people to work full-time in town, as did Philo Chapman, James Terca, Frank Brooks, and Benjamin Seagley, it may have seemed little more than an inconvenience to file a claim, put up a shanty, plant a few acres of corn, and visit the claim on weekends or even less frequently. In fact, as Terca's story indicates, for some males, the most difficult part might have been the lengthy commute between town and claim. Often omitted from these accounts, however, are the experiences of wives and children, who frequently bore the major difficulties of actually living on the claims. No doubt, economics also played a role in an individual's decision to be both homesteader and business owner. The ability to prove up on one hundred sixty acres and then either sell the land at a profit or rent it to produce income might have seemed like an economic edge to local businessmen. For homesteaders who arrived with little capital, financial reality and marginal land often made in-town work a necessity.

The occupations listed in the 1910 census help to form a picture of the economic activities in Presho and similar communities at the time. In 1910, Presho was still a growing community, with a large contingent of workers that included twenty four carpenters, twenty-three laborers, and six draymen. With fourteen men listed as real estate agents, land transactions were clearly still big business in and around the town. Although a few people probably had automobiles in 1910, the presence of six livery barn workers plus a manager and six harnessmakers indicates that area residents relied heavily on the horse for transportation and farm work. Along with the town's six blacksmiths and one tinner, these jobs suggest an economy situated midway between the labor-intensive, craft-centered activities of the nineteenth century and the industrialized mass production of the twentieth century. Lacking electrical, water, and sewer systems, Presho in 1910 had yet to become a modern community. At the same time, the census hinted at change as three occupations—chauffeur, mechanic, and garage manager—all related to motor vehicles.

While most of Presho's residents who listed occupations in the federal census of 1910 were males, a number of females also worked for wages. Of the 275 persons listing occupations, 67, or roughly 24 percent, were women. In Presho, men's and women's occupations generally reflected societal expectations that each sex was best suited to perform particular, usually separate, types of work. In keeping with this nineteenth-century doctrine of separate spheres for the sexes, men were to inhabit the "outside" world, both in work and in political and leisure pursuits, Women, on the other hand, were to live in the "private" world of the home, and focus on their roles as wives and mothers. Unmarried females had always worked outside the home, but once married, they were expected to take on domestic duties full time.

Most of the Presho women listed in the 1910 census worked in traditionally female occupations. They were waitresses, cooks, chambermaids, telephone operators, clerks, seamstresses, and stenographers. The largest occupational category was teacher, with ten women, all single, employed in the public schools and one woman giving private music lessons, The second largest occupational group was servant, with seven females listed. The primacy of these occupations paralleled the country as a whole, with one major difference. In Presho, more women worked as teachers than as servants, a reversal of both national and regional figures. Nelson, in After the West Was Won, notes a similar ratio around Kadoka and attributes the abundance of teachers in west-river South Dakota in 1910 to the fact that the area was newly settled and schools proliferated because the state did not mandate a minimum size for school districts.

In business categories, the most traditional pursuit for women was operating a millinery store. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, almost every town had at least one shop where women could purchase new hats or have old ones retrimmed. Millinery stores also provided women a place to meet and visit in a community where males dominated most businesses. With two hat shops, Presho was no exception to the national trend. Ida Lincoln, a widow with two young daughters, operated one shop, and her business was sufficiently good for her to employ a hat trimmer. While most business or working women in Presho engaged in traditionally female occupations, a few had clearly moved into the ranks of male employment. One woman independently operated a general merchandise store; another a confectionery store; and a third a photography gallery. Several women worked as partners with their husbands, operating a confectionery store, general merchandise store, and a laundry. One served as an abstractor in a land office, and another worked as a newspaper compositor. A number of women also worked as bookkeepers.

Ten years later, in 1920, the federal census reported 597 people living in Presho, a decrease of 38 over 1910. The town still reflected its frontier heritage, with 57 percent of its residents being male. In total numbers, Presho had almost held its own, but the town of 1920 bore little resemblance to the one that existed in 1910. Only 97 of those persons living in Presho in 1910 remained in 1920. In other words, the persistence rate for all residents between 1910 and 1920 was startlingly low, just a little over 15 percent. Of the 157 heads of households counted in the 1910 census, only 31 were still in the community in 1920. Of those, 16 held the same job, while 14 had changed. The other persister had specified no occupation in 1910 but was listed as a farmer in 1920. Considering that Presho had a total of 243 occupations listed in 1920, only about 6 percent of the heads of households had persisted in the same job for a decade. In one of the few studies of business persistence in small plains communities, John Hudson shows that in North Dakota, the ten-year persistence rate for businesses from 1890 to 1900 was 32 percent, while from 1900 to 1910 the rate was only 11 percent. Hudson contends that persistence rates were higher between 1890 and 1900 because times were bad and "people tend to remain where they are when the economy is sluggish." Conversely, in good economic times, when business opportunities abound, people tend to move on and look for new possibilities.

A closer look at the persisters reveals that all were males who worked in various occupations: two real estate agents, two carpenters, one harnessmaker, two lawyers, three merchants, one banker, one drayman, one jeweler, one physician, one pharmacist, and one baker. Their career changes represented movement both into and out of the merchant and managerial classes. P. S. Chapman, for example, went from managing a lumberyard in 1910 to owning his own general merchandise store in 1920. Willard B. Hight changed from building houses to owning a hardware store in partnership with a brother. At the same time, Claude Van Horn sold his saloon and went to work as a rural mail carrier. Reuben B. Wilcox moved from operating a barber shop to working as a hay contractor. George G. Weber had owned a grocery and feed store in 1910, but in 1920 he listed carpentry as his trade. Two men occupied in business in 1910—a real estate agent and a general merchandiser—were ten years later listed as farmer and rancher, respectively. One change clearly represented economic upward mobility. Easton B. Fosness, a laborer who did odd jobs in 1910, did excavation contracting in 1920, presumably operating his own business. None of the other laborers and servants and only one of the teamsters/draymen present in 1910 remained in the community in 1920. Nor were any of the females who engaged in business in 1910 present ten years later, The town-builders of Presho, those who persisted over a decade, were clearly the male professionals, businessmen, and skilled craftsmen.

Although the population itself had largely turned over by 1920, the configuration of Main Street underwent little change as businesses remained located in a three-block area. Moreover, many of the businesses were the same ones that had operated in 1910. The two lumberyards were still open, but with different managers; the three general merchandise stores remained, but with only one of the original owners; the town still had an operating creamery, but one under new management. A different owner ran the furniture and undertaking establishment, and the railroad station had a new agent and subagent.

By 1920, Presho had attracted new businesses, as well, including a second butcher shop and two shoe-repair shops. The addition of occupations that did not exist in the town in 1910 reflected the advance of technology, which created new jobs and made older trades obsolete. Included for the first time in the 1920 census were the occupations of truck driver, electrician, telephone lineman, theater proprietor, garage mechanic, and oil station proprietor. At the same time, the number of blacksmiths declined from six in 1910 to one in 1920; harnessmakers went from six to one; and livery-barn employees disappeared completely. By 1920, Presho residents were using automobiles rather than horses for transportation and were buying standardized, mass-produced equipment rather than relying on custom-made articles and repairs.

The number and type of professionals in Presho had also changed. The town had two pharmacists, two physicians, two nurses, and one dentist in 1910; by 1920, only one physician and one druggist remained, but the town had attracted another nurse and dentist as well as a veterinarian. The 1920 census listed seven public schoolteachers, down from twelve in 1910, and none of them had lived in Presho ten years earlier. At the same time, two of the three attorneys present in 1910 still resided there. Among general workmen, laborers, and servants, nearly all those listed in 1910 were no longer living in Presho in 1920. Little or no information other than the census itself exists about these workers. County histories provide biographies of dozens of long-term Presho residents, particularly business and professional people, but almost no material on those who remained only briefly. The traditional assumption is that people who had little stake in society, owning little or no land or property, tended to move on more quickly than people who did. However, census data show that a number of professionals, craftsmen, merchants, managers, and proprietors had also moved on, suggesting that multiple reasons existed for the tendency of people to relocate within a few years.

Yet another major occupational change between 1910 and 1920 came with females' employment. Of the 243 individual occupations listed in 1920, women engaged in only 28, or slightly more than 11 percent. That figure reflected a considerable decline from 1910 when women made up 24 percent of the labor force. Those who worked outside the home still engaged in the traditional occupations of dressmaker, cook, servant, stenographer, and clerk. The largest female occupational groups were servant and teacher, with seven each. In 1920, only two women operated independent businesses, a notions store and a millinery shop.

During the ten years between censuses, the personal lives of those who had stayed in Presho changed, as well. When Walter Hubbard celebrated his eleventh year of business on Presho's Main Street in 1920, he was a married man with a family. In 1915, he had married a young postal clerk, Alice Jacobson, and the couple now had four children. He had also given up the Chevrolet dealership, believing it was wiser to concentrate on his International Harvester implement business. During the 1910s, as the area experienced agricultural hardships, the Hubbard family had needed the extra income from the cream station and rural mail route. He resigned as mail carrier in 1919 but continued operating the cream station for many years. The lives of other persisters had also changed. Joseph and Mae Stanley, newlyweds in 1910, had three children by 1920. Fred and Mabel Kenobbie had enlarged their family by four children. Don Hopkins, Richard Clute, and Joseph Mahaney had also manned and started families. Richard Sehnert had taken his oldest son in as partner in the bakery. Two men—David Holmes and Easton Fosness—remained bachelors.

Those who remembered Presho in 1910 and stayed into the 1920s would witness a significant change in quality of life over the town's first decade. In 1918, electricity became available, and beginning in 1919, workmen installed a municipal sewer system. These improvements not only made living in Presho more comfortable but also indicated that the town was anxious to be considered a progressive community. Just as dramatic for Presho residents was the change in weather. During the towns founding decade, the west-river country had enjoyed greater-than-average precipitation, which produced excellent crops and lured settlers. Extreme drought hit in 1910 and 1911, destroying any hope of good harvests. From 1912 on, weather conditions improved somewhat but did not return to the glory days of the century's first decade, and farmers experienced numerous crop failures.

That many people left Presho to look elsewhere for employment is documented by the 1920 federal census. What cannot be documented, however, is where the out-migrants went. Did they follow the frontier further west, perhaps homesteading in Wyoming or Colorado? Did some locate in another railroad town farther down the line, where they hoped to be part of another initial boom economy? Or did some families head back east to Iowa, Minnesota, or Illinois in hopes of starting over in a more friendly environment? Equally intriguing is the fact that while some five hundred people left Presho between 1910 and 1920, roughly five hundred more took their place. Despite the region's agricultural difficulties, a large number of people apparently believed that Presho still offered business and employment opportunities.

Preshos experience suggests that there were different types of westem town-builders. For some, like my father Walter Hubbard, the goal was permanence. He would likely have remained in the community under even more dire economic conditions. Others aimed to take advantage of a community's initial expansion, sell out at a profit, and move on. Yet another type appeared to relocate regularly as the frontier moved farther west, perhaps attracted by the excitement of creating a community or hoping to capitalize on developments following the initial settlement period. Still another group sought out any and all opportunities, including both homesteading and operating businesses, to help guarantee economic success. The Great Plains, as many studies of its history and culture have shown, made peculiar and onerous demands of its people. Farmers who settled on the plains required a greater land base, more technological innovation, and larger amounts of capital than did farmers to the east. In the case of the communities that sprang up on the plains, an additional requirement was a continual flow of optimistic, energetic people to replace those who inevitably moved on.

South Dakota History is the quarterly journal published by the South Dakota State Historical Society. Membership in the South Dakota State Historical Society includes a subscription to the journal. Members support the Society's important mission of interpreting, preserving and transmitting the unique heritage of South Dakota. Learn more here: https://history.sd.gov/Membership.aspx. Download PDFs of articles from the first 43 years and obtain recent issues of South Dakota History at sdhspress.com/journal.