Changing Times, Changing Spaces

The South Dakota Stores of J. C. Penney

By: David Delbert Kruger

South Dakota History, volume 40 number 4

When the first J. C. Penney store in South Dakota held its grand opening on 1 April 1916, the celebration took place not in the bustling business district of one of the state’s larger cities like Sioux Falls or Aberdeen, but on Main Street in the tiny farming community of Redfield.

At the time of the grand opening, Redfield was a fraction of the size of Sioux Falls, with a population of just under three thousand.

The small, personable size and agrarian environment of the Spink County seat were, however, consistent with the rural locations the company founder, James Cash Penney, had coveted as he began to expand his chain of stores from Wyoming eastward. As Penney himself reflected, “For me, innately, cities were places to keep away from. Small towns were where I was at home. I knew how to get close to the lives of small-town people, learning their needs and preferences and serving them accordingly.”

Born 16 September 1875, Penney had spent his formative years growing up in near-poverty on a farm in northwestern Missouri. The family’s financial situation was so grim that when young Penney reached the age of eight, his father informed him that the time had come for the boy to start buying his own clothing. With necessity being the mother of

invention, Penney went to work growing watermelons and raising pigs to make money. He also became an apt pupil of retailing, always trying to maximize the quality of the clothing he could afford. As he grew older, Penney took up farming and livestock raising for his livelihood while moonlighting as a clerk in a local clothing store. The risk of develodping tuberculosis forced him to leave Missouri for the dryer climate of the West, where he embraced a full-time career in retailing that ultimately led to his own chain of dry-goods stores.

Between 1916 and 1930, Penney would establish his stores in thirty-four South Dakota locations from Spearfish to Sioux Falls. As South Dakota towns changed with the times, J. C. Penney stores changed, too, first serving customers as main-street icons and, by the last quarter of the twentieth century, as anchor stores in their local malls.

Penney was forty years old when he opened his Redfield store, fourteen years after opening his first one in Kemmerer, Wyoming, in 1902. Within that relatively short span of time, he had amassed a chain of 127 department stores, most of them in Wyoming, Utah, and Idaho. His first stores carried the name “Golden Rule,” the retail chain with which Penney and his first two business partners, William Guy Johnson and Thomas M. Callahan, had been affiliated. Callahan had first employed Penney as a clerk at his Golden Rule store in Longmont, Colorado. Impressed with Penney’s focus and work ethic, Callahan began grooming him for management at an Evanston, Wyoming, store he owned jointly with Johnson. Ultimately, Johnson and Callahan did more than mentor Penney; they also put up two-thirds of the capital investment he needed to open his first store in Kemmerer and helped him acquire three other stores in Wyoming and Idaho. Before long, Penney was able to buy out his partners and offer similar Golden Rule store partnerships to his own associates, allowing his chain to grow.

Just ten years after opening his first store in Wyoming, Penney had thirty-four stores that were rapidly outgrowing and distinguishing themselves from others in the Golden Rule chain. By 1913, three years before he ventured into South Dakota, Penney had decided to break with the Golden Rule franchise and begin “rebranding” his stores with a new name, a process that was completed by 1919. Ironically, it was his associates—and not James Cash Penney himself—who selected his abbreviated name as the designation for his stores. At the time of its opening, the new Redfield store was identified by both the Golden Rule and J. C. Penney names.

After a year of operating in South Dakota, Penney began to expand his presence in the state, opening a new store in Mitchell, followed by one in Huron.

Like many of the early J. C. Penney establishments, the Mitchell and Huron stores were opened using profits from existing stores, which the company often referred to as “mother stores.” Because the financial lifeblood of the entire chain could be traced back to the original store in Wyoming, the J. C. Penney store in Kemmerer became known as the company’s official mother store. Subsequent J. C.

Penney stores carried out the same function, providing not only capital but also potential managers and clerks to staff additional locations successfully. The mother store responsible for the new J. C. Penney location in Mitchell was eight hundred miles away in Richfield, Utah. The Huron store opened with profits pooled from two stores in Utah. As the Mitchell and Huron stores generated profits, they, too, would become mother stores for additional J. C. Penney locations, some within the state. Within ten years, profits from the Huron store would be set aside to open new stores in Aberdeen and Sioux Falls.

As stores carrying the new “J. C. Penney” name began to multiply across the Northern Great Plains and Midwest, Penney soon realized that he could not continue to oversee the operation of every site. “If I had insisted on keeping personal control of the Penney Company,” he later reflected, “we would still be merely a small chain of stores scattered through the Middle West.” Penney’s associates wanted rapid growth and national expansion, but banks were reluctant to lend money to a business that was based on a rather unorthodox system for distributing and reinvesting profits through various levels of partners, managers, and associates. As a result, the J. C. Penney Company was formally incorporated in 1913 and moved its headquarters to New York City the following year. Five years later, the company had grown from 48 stores in seven states to 197 stores in twenty-five states. At the same time, annual sales soared from $2.6 million to $28.7 million.

The J. C. Penney Company identified new locations for stores in South Dakota and elsewhere using a combination of census figures (towns with more than fifteen hundred and fewer than twenty-five thousand people were considered ideal) and personal observations. The company maintained a crew of eight location scouts who visited potential sites and reported back to headquarters in New York on a number of factors, including the rate of growth in a given area, dominant industries, suitable downtown space, and other retail competition. Adhering to the philosophy of its founder, who had found his niche market in rural areas, the company investigated not only towns like Redfield, but in some cases, smaller communities west of the Missouri River like Lemmon and Edgemont that had been established more recently as railroad towns or homesteading centers. Once the

company had determined that a J. C. Penney store could effectively serve a community’s needs and make a reasonable profit, a prospective store manager would be selected. Company officials based such decisions partly on an individual’s managerial ability but also on an assessment of how well the candidate would fit into the community. Keeping with the tradition that had given him his start, Penney provided any ambitious associate not only the opportunity to invest in a new store location, but in many cases, to become its manager. In some instances, new stores were established in order to give a promising manager his own operation to oversee.

More often than not, the J. C. Penney Company succeeded in matching the right manager with the right town. When plans to open the Mitchell store were finalized in 1917, Bradley Young, an enterprising associate from the mother store in Richfield, Utah, became its first manager. He would spend the next thirty-six years in the position before retiring in 1955. Young’s tenure as manager of a single store was among the longest in company history, indicating a shared affection between

Young and the Mitchell community. Other South Dakota store managers had long tenures, as well. L. A. Lemert spent thirty-two years managing the J. C. Penney store in Brookings. The first two managers of

the Watertown location, C. J. Stadtfeld and John W. Smith, oversaw that store for a combined forty-four years. E. F. Fahrendorf managed the Sioux Falls store from the time of its grand opening until his retirement twenty years later. Hans Jorgensen, the manager who replaced Fahrendorf when he moved on from Aberdeen, went on to manage that establishment for twenty-four years.

Even as the J. C. Penney corporation was expanding nationwide from its urban, cosmopolitan headquarters in New York City, Penney himself sought to remain connected to his own rural roots. Although he had turned responsibility for day-to-day operations over to one of his most trusted protégés, a Kansan named Earl Corder Sams, in 1917, Penney remained chairman of the board. As in his younger years, unrelenting work was taking its toll on his health, and he turned to outdoor pursuits to restore his well-being. In 1922, the forty-seven year old Penney purchased Emmandine Farm, an estate about twenty miles north of New York City, as his personal residence.11 In these rural surroundings, Penney renewed his interest in agriculture, a business that directly impacted the J. C. Penney Company. He later wrote: “I had perceived that, since stores in small towns are naturally dependent in great measure on rural people, prosperity for farmers means prosperity for our stores. . . . By the onset of the twenties we had over three hundred stores, located in a large number of states, and my incessant trips among them enabled me to form a clear impression of agricultural conditions and problems. It seemed to me that nearly everywhere I went farmers stood in need of better cattle.” At Emmandine Farm, Penney oversaw the study and development of purebred Guernsey cattle. In 1925, he began a model farming community, agricultural institute, and memorial to his parents on 120,000 acres of land in central Florida that came to be known as Penney Farms. Foremost Dairies Products, Inc., a dairy cooperative named after one of his champion Guernsey bulls, was one of several enterprises that grew out of this Florida project.

The J. C. Penney Company continued to grow rapidly, even without Penney’s direct supervision. In 1920, the firm had expanded again in South Dakota, opening a new location in Rapid City that gave the West

River region not only its first J. C. Penney store, but the only one within a two-hundred-mile radius. Unlike Sears, Roebuck and Company and Montgomery Ward, the J. C. Penney Company did not offer catalog sales until the 1960s.Thus, the firm considered rural residents throughout the entire western half of the state to be part of the Rapid City store’s customer base. Prior to the grand opening, the company took out a full-page advertisement in the Rapid City Daily Journal explaining the J. C. Penney retail philosophy:

Why We Come to Rapid City

First of all—WE ARE HERE TO STAY!

Our investigation of conditions in and about Rapid City has convinced us that the majority of people will quickly appreciate the advantages offered to them by the service of this store. With new goods always, lowest prices every day and courteous services at all times—this “different” store will fill a long-felt want in this community.

People who have heretofore “sent away” for merchandise will find it will pay them to travel hundreds of miles, if necessary, to

partake of the every-day values we offer.

Attend the opening for proof!

You will be quickly convinced this is in truth “the store for everybody.

Within three years of the Rapid City opening, additional J. C. Penney stores began operations in Aberdeen, Brookings, Madison, Watertown, and Yankton. The company timed the Yankton grand opening to coincide with the local county fair, capitalizing on the draw of both town and country residents. According to the Yankton Press and Dakotan, eight J. C. Penney associates served hundreds of visiting customers during the grand opening of the Yankton store.

By 1925, the company had set aside enough profits from the Huron store to move into Sioux Falls, where it opened a store at 129–131 North Phillips Avenue, the former location of Bob and Nels Clothing Store. While the state’s largest city already had a vibrant retailing scene, with businesses such as Fantle Brothers, F. H. Weatherwax, Shriver-Johnson, and Delaney Clothing, demand for a J. C. Penney store had grown steadily. E. F. Fahrendorf, manager of the Aberdeen store, was brought in to open and run the new J. C. Penney. When shipments of fixtures needed to display merchandise had not arrived by the opening date, Fahrendorf considered delaying the event, but he received so many calls from eager Sioux Falls residents that he felt obliged to proceed. The new manager’s optimism overrode any momentary frustration as he told a reporter from the Sioux Falls Daily Argus-Leader: “We have found many people in Sioux Falls who have traded at J. C. Penney company stores in other places and who said they were glad to see our new store opened here. Two years ago the opening of the Aberdeen store was more than satisfactory, and indications are that the Sioux Falls store will far exceed the Aberdeen store both as to the opening day and continued business. We have secured practically all our employees from Sioux Falls so the people will be greeted with familiar faces.

On 25 September 1925, the Sioux Falls J. C. Penney opened at nine o’clock in the morning and remained open until nine that evening. With the addition of the Sioux Falls store, where customers could purchase women’s dresses for $.79 and men’s work overalls for $1.39,19 the total number of J. C. Penney stores in South Dakota had reached ten. Soon thereafter, the company began planning a wave of openings that would triple the number of J. C. Penney stores throughout the state and increase the company’s presence nationwide almost exponentially.

The expansion of the J. C. Penney chain in the late 1920s saturated more South Dakota cities and towns than any other retailer

before or since. In addition to opening new stores in De Smet and Wessington Springs in 1927, the company bought out the Jones Golden Rule chain and converted its stores in Canton, Chamberlain, Deadwood, Lead, Milbank, Mobridge, Pierre, Selby, and Sisseton to J. C. Penney stores. Not every venture thrived; the stores in Deadwood and Selby were closed within two years.

The twenty stores operating successfully during this period, however, had a considerable impact on the state’s economy, which the company did not hesitate to highlight. In 1927 alone, company officials claimed, J. C. Penney stores directly contributed $428,510 to the South Dakota economy through taxes, real-estate improvements, associate salaries, and South Dakota-made goods sold nationwide through other Penney’s establishments.22 The next year, J. C. Penney stores opened in the college towns of Vermillion and Spearfish. In 1929, the company opened nine more new stores throughout the state, four in the East River towns of Britton, Clark, Miller, and Scotland, and the remaining five west of the Missouri River in Lemmon and in the Black Hills towns of Belle Fourche, Sturgis, Hot Springs, and Edgemont. By the end of the decade, J. C. Penney had over thirty stores operating throughout South Dakota. Nationwide, nearly four hundred new J. C. Penney stores opened in 1929 alone, bringing the total to more than one thousand and giving the chain at least one store in every state.

From Edgemont to Milbank, all of these J. C. Penney locations were full-fledged department stores, selling everything from fashionable women’s apparel to men’s overalls. Most of the stores’ inventories were devoted to women, with selections of “ready-to-wear” dresses, hats, fur coats, and undergarments, as well as linens and fabrics for making family clothing. Within the same stores, however, farmers could buy Pay Day overalls, Big Mac work shirts, and gloves and overshoes for hard labor, in addition to Towncraft suits or Marathon fedora hats for church and special occasions. Children and infants typically had separate apparel departments, while the shoe department carried casual, work, and formal footwear for women, children, and men. The company gave store managers considerable control over inventories in order to match the demands of customers within individual communities. In college towns like Brookings and Vermillion, for example, inventories were tailored to accommodate student apparel.

J. C. Penney managers could also bring in other product lines, such as accessories, kitchenware, luggage, dining sets, and silver flatware, if they believed the items would sell. The ability of managers to select

merchandise gave each store variation and unique appeal to local customers. Also attractive to customers was the company’s cardinal policy of allowing the return of J. C. Penney merchandise to any J. C. Penney store, regardless of where the purchase had been made. This convenience was particularly appealing for rural residents like those in Harding County, whose farm or ranch business took them variously to Belle Fourche or Lemmon, South Dakota; Bowman, North Dakota; and Baker, Montana, each of which had its own J. C. Penney store.

Aside from being department stores in form and function, Penney’s early South Dakota stores bore little resemblance to their modern shopping-mall counterparts. Originally located downtown, typically on main street, the majority of J. C. Penney stores had narrow, yellow-and-black-tiled storefronts with relatively small interior square footage. The first Vermillion store, for example, stretched back one hundred thirty feet from its Main Street sidewalk but was only thirty feet wide, creating a sales floor of less than four thousand square feet. The Spearfish store was even smaller, just twenty-seven feet wide with a sales floor of twenty-seven hundred square feet. All stores had showcase display windows to attract shoppers in from the sidewalk, although some windows were just large enough to display two mannequins at a time.

In smaller towns, Penney typically opened with what he called a “single-room” store, essentially a building with one narrow, open area for the main sales floor. In cities like Sioux Falls and larger towns like Huron,

Mitchell, and Yankton, J. C. Penney stores opened with “double-room” sales floors that were twice as wide; support columns placed down the center typically divided the two halves. In some cases, smaller towns like Chamberlain, Lemmon, and Wessington Springs also opened with double-room stores, while the single-room store that opened in Mobridge occupied one-half of an existing building and had the option of expanding into the remainder to create a double-room configuration. This plan was cost-effective and pragmatic for J. C. Penney stores located in communities whose future growth was uncertain. If the town’s

population and the store’s sales increased, expanding into a double-room configuration was relatively easy.

Regardless of a store’s size, Penney clearly preferred symmetrical storefronts and interior layouts, and nearly every early store that opened across the state was designed along these lines. The entrance occupied the center of the facade and opened onto a clear interior pathway that divided the sales floor in half from front to rear, with the various departments arranged neatly on both sides. In addition to hardwood floors and high, stamped-tin ceilings, one of the most distinctive interior features of many early J. C. Penney stores was a rear balcony, clearly visible upon entering the store, with a

staircase typically leading up from the left side of the sales floor.

The early function of these balconies was specifically for handling transactions, as J. C. Penney stores sold merchandise on a “cash-only” basis, and currency was not usually exchanged or stored on the main sales floor. Thus, whenever customers purchased items from stores with balconies—such as those in Huron, Mobridge, Rapid City, or Yankton—the sales clerk would take the customer’s money and place it with a bill of sale into a closed container, which would then be attached to one of the wires, or “zip lines,” that extended from various points on the main sales floor to the balcony. With the pull of a rope, the clerk released a spring that launched the carrier along the wire to its destination. Another associate in the balcony would retrieve the cash, make change, and send the container back down. In some stores, pneumatic tubes eventually replaced zip lines until secure cash registers made the remote transactions unnecessary. The store’s rear balconies then became the primary location for children’s clothing, often with the shoe department situated directly below.

As the J. C. Penney chain grew to one thousand stores nationwide, James Cash Penney and his partners could seemingly do no wrong. Misfortune occurred, however, when they took the company public and gained listing on the New York Stock Exchange in 1929—less than one week before the stock market crashed. The aftershock, in the form of the Great Depression, caused total J. C. Penney sales to drop by more than nineteen million dollars by the end of 1931, with further losses the following year. Although the company’s stock did not completely bottom out, its founder was left broke. For the previous twenty years, Penney had taken no salary but instead chose to live off of and reinvest store profits from his partnerships. Compounding his financial woes, he had placed his entire fortune of J. C. Penney stock as collateral for various philanthropies. Finally, any savings he did have were wiped out when the Florida bank where he served as a director folded. For all of his success, these events of the early Great Depression left Penney regarding himself as a complete failure. Well aware that Penney’s own generosity had brought him to the brink of ruin, more than one thousand of his associates came to his financial rescue, donating portions of their own salaries and stock shares to help him recover.

The year 1932 was certainly the economic nadir for most J. C. Penney stores across the country, and those in South Dakota were no exception. Between 1929 and 1932, annual sales at the Brookings store alone plummeted from $146,000 to $84,000. Despite the hardships of the Great Depression, the J. C. Penney Company was still able to expand in South Dakota during the 1930s. At the beginning of the decade, additional stores opened in Webster and Winner, along with nearly 150 others nationwide. True to its origins, the company had remained focused primarily on smaller cities and towns, rather than large urban centers. To be sure, by 1930, every town in South Dakota with a population of ten thousand or more had its own J. C. Penney store, but so did more than half of all South Dakota towns with a population of one thousand or more. One year after opening the store in Winner, however, the company began a concerted shift into metropolitan areas, building a massive, six-floor department store in downtown Seattle, Washington, that had sales of $1.5 million during its first year of operation. Such success gave company officials the confidence to open gigantic J. C. Penney stores in other large cities throughout the nation, enabling it to compete with Sears and Montgomery Ward, which had expanded from catalog sales into retail outlets. Thus positioned, the J. C. Penney Company was ready to follow the later shift of population to the suburbs, a move that ultimately made the department store a presence in communities ranging in population from a few hundred to millions.

Not every J. C. Penney store in South Dakota emerged successfully from the Great Depression. The company had been forced to close its places of business in Canton, Edgemont, Webster, and Wessington Springs. By 1934, however, its national sales had recovered completely, and twenty-eight South Dakota cities and towns still had J. C. Penney stores in their central business districts. Once the depression subsided, the company began to expand and remodel its existing locations. In towns like De Smet and Sturgis, with stable rather than growing populations, J. C. Penney stores were remodeled, while a booming population and greater customer demand in Sioux Falls drove the company to relocate that store to a much larger building. The new Sioux Falls J. C. Penney store at 115 South Phillips Avenue, situated next to Montgomery Ward and soon flanked by the new F. W. Woolworth building, was located one block south of its former site and opened in 1939.

Even as the economy improved during the post-Depression era, other factors posed challenges for the operation of J. C. Penney stores in South Dakota. When the United States became involved in World War II, managers and employees took leave to serve their country. Harold I. Reilly, manager of the Madison store, served in the armed forces from 1942 to 1946 until returning to his position, which the company had filled using temporary managers.34 Disasters, both natural and human caused, occasionally befell the buildings housing J. C. Penney stores. A fire started in the downtown Huron store on 7 April 1938,

completely gutting the interior and weakening the building’s structural support. Although the facade survived the immediate fire, the weakness of the remaining structure soon caused the entire building to collapse into rubble. The J. C. Penney Company quickly cleaned up the destruction and built a new store on the old location.

Fire would also destroy the Mobridge store years later, although the company used the disaster as an opportunity to open a larger, modern store in a new building just up Main Street. The J. C. Penney store serving the state capital had an entirely different problem during the Missouri River flood of 1952. Although floodwaters swamped most of downtown Pierre, especially the lower levels of South Pierre Street, a levee of sandbags saved the J. C. Penney building from catastrophe, and the store was able to reopen in the same building after the waters receded.

The majority of J. C. Penney stores in South Dakota weathered these and other adversities to survive well into the postwar years. The Canton, Edgemont, Webster, and Wessington Springs stores had fallen victim to the depression, and the Scotland store had closed shortly there after, but nearly thirty of the thirty-four J. C. Penney stores established in South Dakota were thriving as the second half of the twentieth century began. Nationwide, the J. C. Penney Company continued its rapid growth. In 1951, nearly fifty years after its humble start as a single store in Kemmerer, Wyoming, the company topped sixteen hundred stores and the $1 billion sales mark, a financial accomplishment that Penney himself had predicted in 1927.

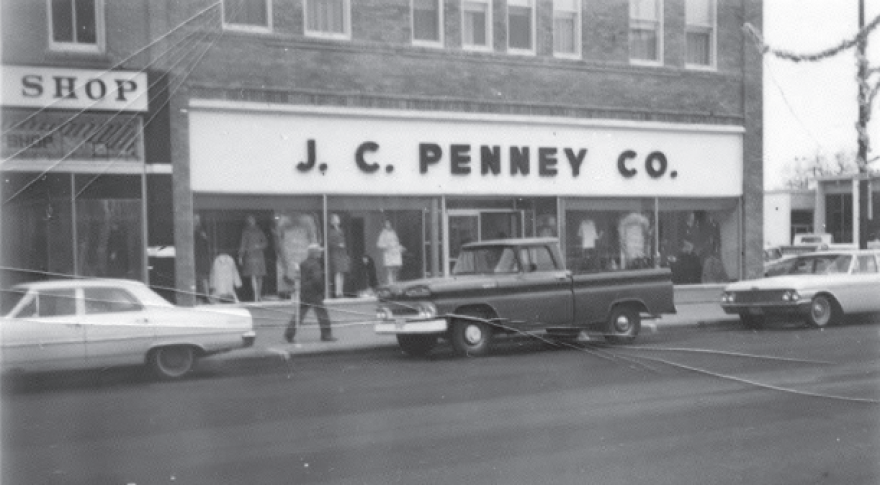

Throughout the 1950s, J. C. Penney modernized its stores across the state, extensively changing their appearances inside and out. As prosperity returned to South Dakota’s main streets following the lean depression and war years, competing department stores such as Fantle’s, Shriver’s, Sears, and Montgomery Ward also underwent modernization. In order to remain competitive and serve the growing populations of Brookings, Pierre, Rapid City, and Sioux Falls, the J. C. Penney stores in

these locations were expanded and comprehensively remodeled, making each one as up-to-date as any modern department store in the nation. Nearly every J. C. Penney store in South Dakota experienced some form of upgrade during the decade. If company officials had confidence in a store’s location, even those in smaller towns like Belle Fourche and Lemmon received a thorough update in appearance, making the building itself a modern and fashionable institution within the downtown business district.

For some J. C. Penney stores, these renovations were the first significant changes made since their

openings, and customers welcomed the modernization of form and function. Prior to the 1950s, the exteriors of most J. C. Penney stores across South Dakota featured painted steel signage, glass fronts, and wooden doors. The masonry of the original buildings had seldom been altered, and large sections of glass, either in the form of flat panes or glass blocks extending across the upper front, were prominent in nearly every store across the state. The company’s designers had historically used glass as an economical way to enhance interior lighting, but by the 1950s, the look had become antiquated. The glass sections also prevented the use of larger signage across J. C. Penney storefronts. As Woolworth dime stores modernized and Montgomery Ward and Sears emerged as serious competitors in the department-store arena, improving the visibility of J. C. Penney stores within downtown business districts became extremely important.

Through the use of better interior lighting, the J. C. Penney Company could afford to cover the glass above a store’s entrance and, usually, the entire upper storefront with a smooth cladding facade done in a color that

better distinguished it from the surrounding competition. In the case of the Rapid City store, green cladding not only modernized and set the storefront apart but also masked the store’s expansion into an adjacent building, giving the appearance of one large, cohesive structure. Stores in Belle Fourche, Lemmon, Spearfish, Sturgis, and Yankton received similar “facelifts.”

Once the modern facade was in place, the company could install larger, individual “J. C. PENNEY CO.” letters above the store’s entrance that were easily visible from sidewalks or the street. For corner locations, such as those in Brookings, Pierre, and Yankton, the company also affixed horizontal letters on the side to provide visibility from both intersecting streets. Stores situated in the center of a city block sometimes gained a vertical sign that protruded outward and extended above the top of the storefront, allowing pedestrians and drivers alike to see the location from two or three blocks away. These signs were typically illuminated at night to keep the stores visible during evening hours.

In the course of making these major exterior upgrades, the company altered other features, as well. The mosaic tile around the entrance and showcase windows that had matched the old yellow-and-black metal signage was frequently covered over, usually with material that matched or harmonized

with the upper storefront cladding. Stainless-steel doors and casings with large glass panels also replaced the traditional wooden doors, as the brighter metal was deemed more fashionable and cohesive with the look of the rest of the modernized storefront. In addition, canvas sidewalk awnings were often eliminated in favor of fixed metal awnings or, in extensive remodels such as those at Rapid City, Sturgis, and Yankton, by incorporating a covered vestibule within the center of the storefront.

Remodels of store interiors also reflected the company’s desire to be viewed as a modern, fashionable department store. The dark, highmaintenance hardwood floors

were completely covered by tile placed down the center aisles and auburn carpet laid over the sales floors on either side. The stamped tin ceilings disappeared, covered over with smooth drop ceilings that could accommodate new fluorescent light fixtures that brightened the sales floors and compensated for the loss of natural light that had previously come through the glass-block walls.

In larger stores, the company also installed illuminated directory signage that routed customers to departments on the upper floors or, if merchandise was available in a basement location, to the “Downstairs Store.” Secure cash registers allowed the company to remove its remote cash conveyors and cables, freeing up rear balconies for merchandise and making purchases more convenient for the customer. As an upgrade to furnishings, stainless-steel-and-glass sales counters replaced their wooden predecessors, and nearly every new display fixture was chrome-plated. Full-bodied mannequins and illuminated showcases were increasingly utilized to display merchandise in the storefront windows and on the sales floor throughout the store’s departments. Finally, air-conditioning was a welcome addition for associates and customers alike.

New buildings planned for J. C. Penney stores in South Dakota incorporated these interior and exterior modernizations into their very designs. In 1951, the company constructed a four-level store at 401–405

South Main Street in Aberdeen, adjacent to a new Woolworth store. Towns substantially smaller than Aberdeen also gained newer, larger J. C. Penney stores in their central business districts. In 1955, the J. C. Penney store in Lead relocated to a completely new downtown location in nearby Deadwood. Similarly, the Winner store more than doubled its size when it moved to a larger, modern building on the corner of Fourth and Main. All of these buildings featured highly visible storefronts and offered customers a modern shopping experience.

New stores, expansions, and significant remodels were always accompanied by grand-opening celebrations, but the new J. C. Penney store in Mitchell opened to the greatest company fanfare of any Penney’s store in South Dakota. Planning had begun in the late 1950s to replace the store at 223 North Main Street, where the company had done business since 1926. Penney himself was well aware of the store and its community, having known manager Bradley Young since the original Mitchell location opened in 1917, and having visited the city twice during Young’s tenure. Young had retired and passed away before the new store on North Main came to fruition, and his successor, John A. Milne, died less than a year before it opened, prompting the company to promote the manager of the Winner store to succeed him.

When the grand opening finally took place in 1960, the event was significant enough for James Cash Penney to travel from New York City to Mitchell to preside personally over ceremonies at the new location. Other Mitchell retailers such as Montgomery Ward, Thune’s, and Woolworth’s even bought advertisements in the Mitchell Daily Republic congratulating the J. C. Penney Company on the new facilities. On 6 January 1960, the eighty-four-year-old Penney formally addressed the Mitchell Chamber of Commerce, paying tribute to the late Bradley Young and discussing the virtues of competition. The next morning, Penney joined Mayor Martin Osterhaus in front of the store at 412 North Main, just two blocks south of the Corn Palace. Evert J. Van Westen, the manager transferred from Winner, introduced Penney to the large crowd and remarked, “This is one of the nicest stores in this part of the country. We aim to keep it that way.” Penney then ceremoniously cut the ribbon and opened the doors.

Other South Dakota locations gained modern buildings designed exclusively for the J. C. Penney Company, as well. The stores in Madison and Vermillion had remained mostly unchanged since their openings nearly forty years earlier, constricted by a lack of space adjacent to the narrow original structures. In 1962, the company built a new J. C. Penney in Madison at 203 North Egan Avenue, just north of the old location. That same year, the new Vermillion store opened at 9 Court Street, across from the post office on the site of a former lumberyard. Featuring wider, modern storefronts and expanded sales floors, these stores were considered major additions to the central business districts of both college towns.

The death of James Cash Penney ultimately portended the end of main-street J. C. Penney stores in South Dakota. Although Penney had no plans to retire from the company that bore his name, his long and eventful life came to an end on 12 February 1971, when he passed away from a heart attack at the age of ninety-five. With his death came a new era for the J. C. Penney Company and its stores, under the leader ship of Donald V. Seibert and William R. Howell. Company executives soon replaced the “Penney’s” trade name with the modern “JCPenney” logo that is still used today. More importantly, Howell initiated a series of studies examining the consumer market, including whether or not J. C. Penney stores should continue to be located on the main streets of smaller towns.The outcomes of these studies would have a profound impact on J. C. Penney stores throughout the state.

At the beginning of the 1970s, downtown districts across South Dakota still constituted each community’s primary shopping locale, just as they had done historically. More than twenty J. C. Penney department stores were still doing business in South Dakota in 1970, and every one of them operated out of a downtown location. Although the company had already opened mall stores in Minneapolis, Denver, Omaha, and even smaller cities like Alexandria, Minnesota, and Norfolk, Nebraska, it remained committed throughout the first half of the decade to keeping its South Dakota stores downtown. When fire destroyed the Mobridge store in 1970, the new J. C. Penney that replaced it reopened on the same street downtown. When Sioux Falls grew large enough to build its first

regional indoor shopping center at the corner of Western Avenue and West Forty-first Street, J. C. Penney remained in the downtown area, despite the fact that the store’s Phillips Avenue neighbor, Montgomery Ward, had chosen to relocate as one of the anchors in the new Western Mall. The company also passed up other opportunities to move its downtown stores to early indoor malls in Aberdeen, Brookings, Mitchell, and Yankton.

In mid-decade, when planning began for a new shopping center on West Forty-first Street near Interstate 29 in Sioux Falls, J. C. Penney executives decided the time was right to make the move from downtown to an expansive indoor mall. Like its competitors Sears and Montgomery Ward, J. C. Penney had expanded its product lines to include large appliances, sporting goods, and, in some cases, tires, batteries, and oil

sold at J. C. Penney auto centers located near its department stores. Although the downtown Sioux Falls store had five levels, the selling space was inadequate to accommodate all of these product lines, and the area offered no room for expansion. Moreover, downtown shoppers had to pay for parking and battle the elements, in contrast to the new Empire Mall, which offered free parking and a climate-controlled environment.

In 1975, J. C. Penney closed its Phillips Avenue store and opened its new store in the Empire Mall, where it became the first J. C. Penney establishment in South Dakota to be located outside a downtown business district. Within five years, J. C. Penney stores in Rapid City, Brookings, Huron, Pierre, Watertown, and Yankton would also vacate

their downtown premises to become shopping-mall tenants. Like the Sioux Falls location, the new Rapid City store at Rushmore Mall would feature an automotive center and a beauty salon, as well as its own restaurant.

By 1981, nearly every South Dakota city with a population of ten thousand or more had an indoor mall as its primary shopping

destination, and J. C. Penney had relocated downtown stores into seven of these shopping centers. While J. C. Penney stores still remained downtown in Aberdeen, Mitchell, and Vermillion, the centers for South Dakota retailing were increasingly shifting away from downtown business districts. The decline of downtown was evident not only in larger cities with regional malls, such as Sioux Falls and Rapid City, but also in smaller J. C. Penney communities like Lemmon and Milbank, where town and rural customers alike now drove to Dickinson, North Dakota, and Watertown, respectively, to shop for merchandise at climate-controlled malls.

Within the Black Hills region, eight J. C. Penney department stores had operated from the 1920s to as recently as 1982, including those at Deadwood, Sturgis, Belle Fourche, and Spearfish.50 Each of these smaller stores began losing sales and profits because of declines in the local agricultural and mining industries, but the losses were chiefly due to the migration of local shoppers to the Rushmore Mall. With a J. C. Penney store of more than one hundred thousand square feet, as well as Sears, Herberger’s, Target, and over one hundred specialty shops, the Rushmore Mall attracted shoppers from the entire western half of the state, as well as parts of Wyoming, Nebraska, North Dakota, and Montana. Similarly, the J. C. Penney at the Empire Mall in Sioux Falls drew sales away from smaller Penney stores in that region, including locations in southwestern Minnesota and northwestern Iowa.51 In essence, the J. C. Penney stores situated in regional malls were becoming regional stores, and their presence made it difficult for the smaller, downtown J. C. Penney stores in the same area to survive.

In 1983, the company formally addressed this national trend by issuing a “repositioning announcement.” As the final report on the company’s economic studies begun in the 1970s, this document officially shifted the location of J. C. Penney stores from small, rural downtowns to the anchor positions in larger, suburban shopping malls. The company immediately began evaluating the smaller stores, noting that unprofitable stores outside of major metropolitan markets would be

permanently closed, while those with profit potential would either be expanded or relocated to shopping centers.

Although the decisions on store closures were ultimately made in New York City, their impacts were soon visible throughout South Dakota. By the end of the decade, J. C. Penney department stores had disappeared from nine towns across the state, leaving vacant storefronts as reminders of the once-thriving businesses that had stood on their main streets for nearly sixty years—seventy years in the case of Redfield. In Mitchell, the store Penney himself had dedicated in 1960 was closed in 1985, and a new J. C. Penney store occupied space in the Super City Mall. By 1990, after the downtown Aberdeen store had closed and its replacement opened in the Lakewood Mall, only the stores in Madison, Mobridge, and Winner remained in downtown locations. With the closure of the Madison J. C. Penney store in 2002, one hundred years after James Cash Penney first began his enterprise in Wyoming, the company effectively ended its era of main-street department stores in South Dakota.

Today, only twof J. C. Penney stores still do business in South Dakota. That small number belies the impact that Penney’s stores once had, economically and socially, across the entire state. From the most rugged sheep rancher in Harding County to the most cosmopolitan socialite in Sioux Falls, no twentieth-century South Dakotan was ever very far from the fashions and values a J. C. Penney store offered. James Cash Penney’s success in establishing his department store in thirty-four South Dakota communities was a remarkable accomplishment that no retailer is likely to repeat in the foreseeable future.