Growing up, thriller author Megan Miranda spent time at her grandparent's house in the Poconos. There wasn't any cell service — it was just her and her family out there in the woods, cut off from society. "During the day, it would be this grand adventure," recalls Miranda. "But at night I would just stare out into the darkness thinking, 'what is out there?' "

So began Miranda's long obsession with the duality of nature — at once, a beautiful serene place, and also, with just a slight change of perspective, a terrifying one.

"You step inside the woods and it feels like legends can almost be real," she says on a recent hike near her home in North Carolina. "It's a place where things are hidden, but also you can hide. It's just a great place for thrillers."

Nature — woods, lakes, and the ocean — has become a consistent, often menacing character in Miranda's more than a dozen thrillers. Her latest novel, The Last To Vanish, takes readers to a small hiking town in North Carolina, pushed up against the Appalachian Trail. There, 7 people have disappeared in the woods over the last 25 years. Were they all accidents — hikers doomed by nature — or was it something more sinister?

As we hike through the wetlands trail near Miranda's home, the green trees glisten from recent rain, the air thick with moisture. The woods are lush and full in mid-July and you can't really see past 20 feet. It was on a hike just like this that the idea for Last to Vanish came to her.

"It had just rained," explains Miranda as we walk, "and inside the woods, it still sounded like it was raining. I took out my phone right then and started taking notes. It reminded me of this idea of echoes of the past, of a town where everything you are seeing already happened. I went home and started writing immediately."

That seed of an idea turned into a much more complex web. The main character, a young woman named Abby, is an outsider who moved to the small fictional town of Cutters Pass a decade ago. She works at the inn at the base of the mountain, the last place so many hikers were seen alive.

From The Last To Vanish:

He arrived at night in the middle of a downpour. The type of conditions more suitable for a disappearance. I was alone in the lobby, removing the hand-carved walking sticks from the barrel behind the registration desk, replacing them with our stash of sleek navy umbrellas when someone pushed through one of the double doors at the entrance. The sound of rain cascading over the gutters, the rustle of hiking pants, the screech of boots on polished floors. A man stood just inside as the door fell shut behind him, with nothing but a black raincoat and some sob story about his camping plans. Nothing to be afraid of. The weather. A hiker.

The room where Miranda writes her thrillers is on the second floor of her home in Davidson, North Carolina. There are elements of her new book around the room: hiking sticks she and her husband got on a trip to the Great Smoky Mountains lean against a bookshelf and there are pictures of her and her family hiking, hung up around her desk.

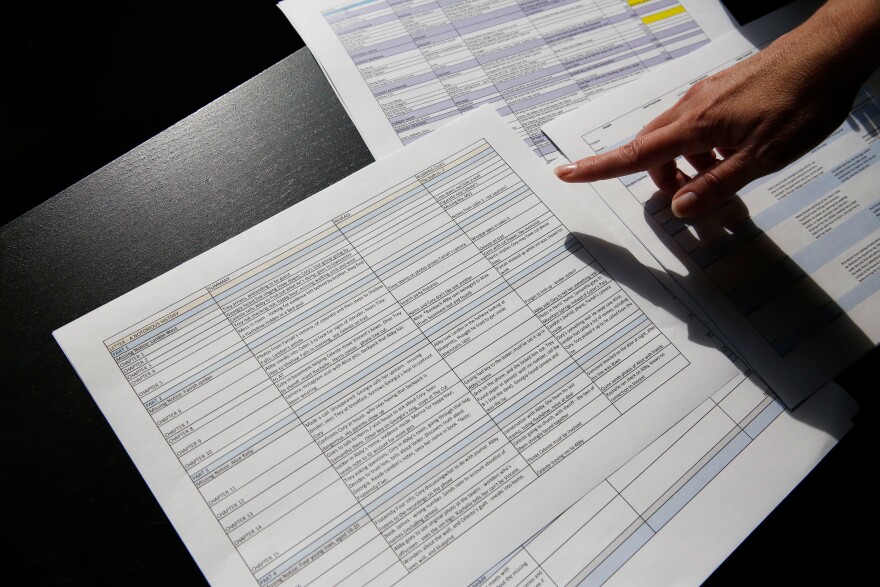

Her method of writing includes keeping spreadsheets that detail the story. "I don't have a murder wall," Miranda explains with a laugh, "it's all on a piece of paper." Columns include dates, plot points, major turning points (ex: a body is found), and clues (ex: there's glass in her toes, blood in the hall but nowhere else.)

She pulls out the spreadsheet for The Last To Vanish. "I'll try not to give any spoilers," she says as she trails her finger down the page. It lands on a clue halfway down: a window is left open in a cabin. "I remember writing that and thinking like, is that something I will use or is that something I won't use?" she says. It's not giving away too much to divulge that the open window ends up being important.

A thriller writer who is scared of many things

On our hike, we pass a pond filled with frogs. We stop to listen, enchanted by the sounds of the woods. The recent rain has made the trail muddy, and as we navigate a few patches, I notice Miranda is deep in thought; her writing brain spinning. Spending time in the woods can do that to you.

"Right now, I was like, 'What would this be like to run on when it's a little muddier?' How can I use that? It changes so much, whether it's been rainy, or what season of the year it is." She looks off to the side of the trail, into the dense landscape of trees and bushes. "You know, we're focused on the trail right now, but there's this whole other part to it where you'd get quite tangled if you ran away," I ask her if she's always thinking about running away. "I'm not," she says laughing, "I just have that on my mind."

Growing up, Miranda's mom was an avid mystery book reader who brought her daughter to the library once a week. Miranda remembers leaving the library holding a stack of books. Nancy Drew was an early favorite — but she's always loved books that had an element of wilderness to them: Hatchet, Where The Red Fern Grows, and Bridge to Terabithia.

The question of the unknown — the what-ifs — was always alluring to Miranda, who started solving mysteries, first in the field of science — working in biotech after college and becoming a high school science teacher — before she tried her hand at writing thrillers.

As we make our way down the trail, I ask Miranda what scares her. "I have an overactive imagination, so I am afraid of many things," she says. She's especially afraid of being alone in the woods at night. Feeling vulnerable and on edge, not knowing what else is out there. "The idea that you hear footsteps behind you and you can't see it and they stop when you stop," she says, "that to me is this terrifying idea." That feeling when the hair on the back of your neck stands up, you feel the tension in your shoulders, and you have a sharp focus on just getting to safety — that's the feeling Miranda is trying to capture in her books.

And yet, it's intriguing that someone who spends her life writing books with tension and murder is seemingly afraid of most things. How does someone who scares so easily, not just read — but write — thrillers?

"I think it's almost a safe way to explore it," she says, "It is like you're taking a journey and you know you're making it through to the other side. I think there is a comforting element and that relief at the end of it." Because in fiction, unlike in life, the murders and the mysteries have a resolution, or an answer or an explanation, which is really the safest way to feel scared.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.