The story of how the digital age came to be involves a cast of more than 40 people, ranging from a 19th century English countess to California hippies. In his new book, The Innovators, Walter Isaacson profiles many of those characters, focusing on how their collaborations helped bring us into the digital age.

Isaacson has long held an interest in creative minds. He's written highly regarded biographies of Benjamin Franklin, Albert Einstein and Steve Jobs. But, as he tells Fresh Air's Dave Davies, his latest book is an attempt to shift away from writing about one person's creativity.

"One of the things we biographers realize is that we distort history a little bit," Isaacson says. "We make it sound like there's some great individual in a garage or a garret who has a light-bulb moment and all of a sudden innovation happens. But when you look at innovation, especially in this day and age, it happens in teams — creativity is a collaborative effort in the digital age. I wanted to get away from writing about the singular individual."

Interview Highlights

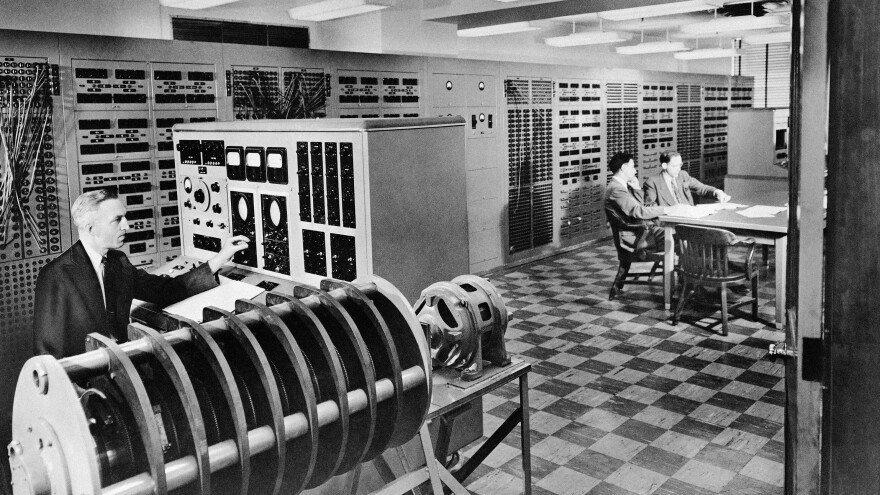

On early computers

They were big ol' things with vacuum tubes, so they glowed and they let off heat. They looked like things in those old movies with the blinking lights. They took up ... the room and most of them were used for wartime uses. ... Colossus was used to break the German codes; ENIAC [Electronic Numerical Integrator And Computer] did missile trajectories, but then a group of women helped reprogram it so it could do atom bomb tests.

On why the Internet is decentralized

The people who were designing it decided for two reasons not to centralize control of the Internet. One ... given by the colonels in the Pentagon is they wanted to make sure that the Russians couldn't send a nuclear attack on some hub and destroy our communication system. So they wanted a system that was distributed.

But the people who were actually building this system, they weren't really thinking about Russian attacks. They were kind of rebellious anti-authoritarian types — they wanted power to the people. They called it "computing power to the people." And so they created a system in which every node on the Internet has the ability to store, to forward, to originate information. ... This decentralized system made it hard for the Russians to blow it up, but it also made it hard for the government or corporations to control the Internet. ...

The Internet could've been designed by the Pentagon or some big corporation. ... Instead, nobody really wanted to build this thing, so it was done in sort of an ad hoc manner. ... It sprang out from the ground up, as opposed to being dictated from the top down — which is the way it could've happened, in which case we would have an Internet that would have a lot of on and off switches that our politicians could control.

On the public's feelings about government involvement in computer development in the '40s and '50s

[Like today], a lot of people believed it was sinister back then. ... This is of course when George Orwell's 1984 is coming out. It was published in 1948 and people thought that computers would lead to Big Brother-like government. But the people who were developing both the Internet and then the personal computer realized that you had to make it personal — you had to give access and power to each of the individuals and that would help the system from becoming Orwellian.

On how San Francisco Bay Area culture gave birth to the personal computer

What you have in the Bay Area of California in the 1970s is a cultural brew that is very anti-authoritarian and it becomes sort of a caldron in which the personal computer can be born. Out in Boston, near MIT, and in Philadelphia, where they did ENIAC, there wasn't this ferment. [The] companies there never thought, "Oh, we're going to want to have personal computers." They were just building office computers that people would share.

But out in the Bay Area and Silicon Valley, you have people who have been part of the anti-war movement. You have hippies who've [read Tom Wolfe's] The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test with [protagonist] Ken Kesey and others who are rebellious and believe in power to the people. You have people following Stewart Brand who read [his book], Whole Earth Catalogue, which has as its philosophy access to tools; and they want to take back this computing power and really make it something that they can use personally and use it as organizing tools and rebellious tools. This is where the personal computer comes out of this brew in California.

On the sealed-up nature of modern technology

One of the things that bothers me is that we used to be able to solder our own circuits when we were making our ham radios. And nowadays, when you have an iPhone or iPad or, for that matter, even a laptop, you're not supposed to open it up. You don't know what goes on inside. So that ability to tinker and solder and to even know what a circuit is, why an on/off switch — which is basically all a transistor does is flick things on and off — why on/off switches can make logic happen. Those are very important things. So I would hope that there would be a way in the future where we wouldn't just understand the software, but we would have a better feel [for it]. ... Certainly if you look at all the great people of the digital age ... they loved that hands-on imperative, to be able to take it apart, to be able to fiddle with it. I fear that our machines these days are a little too sealed up.

Copyright 2023 Fresh Air. To see more, visit Fresh Air.